罗马帝国语言

-“我们要裸体了”([N]os nudi [f]iemus);

-“我们是来喝酒的”(Bibere venimus)

-“你们真能说”(Ia[m] multu[m] loquimini)

-“我们可能会被叫走”(Avocemur)

-“我们要喝三[杯]”(Nos tres tenemus)

这一幕可能表达了“成事不说,遂事不谏,既往不咎”“人生苦短,及时行乐”之类意义的谚语。[1]

拉丁语是罗马帝国的官方语言,但以希腊语为代表的其他语言在地方上也很重要。拉丁语是罗马人的母语,在整个古典时期一直是帝国行政、法律、军事的标准用语。[2]在帝国西部,拉丁语甚至被用于法院等地方行政用途。[3][4]所有自由出生于公元212年的男性居民普遍获得公民权后,产生了许多不能通晓拉丁语的罗马市民。不过,此时拉丁语仍是“罗马身份”的象征。[5]

公元前4世纪末亚历山大大帝的征服使得通用希腊语成为了地中海东部地区的通用语和与东侧境外政权外交的用语。希腊语的跨国境使用是基督教化的必要条件,例如《圣经新约》的语言选定为希腊语,便是考虑到其影响广泛,使用人数众多。[6]罗马帝国教会的大公会议也使用希腊语,而不用拉丁语。随着罗马帝国的衰落,希腊语在东罗马帝国取代了拉丁语,成为了更加主要的语言。

由于古代社会交流主要发生在口头,因此很难确定罗马治下各种地方土语的应用都发生在什么场合。铭文中的蛛丝马迹及希腊、罗马文献中,均反映了罗马人与外国人交流时对翻译的需求。布匿语、科普特语、阿拉米语有大量铭文及书信得以保留。[7]凯尔特人的语言遍布在西欧大部分地区,虽然凯尔特语言的口述记录相当稀少,[8]但凯尔特语铭文数量有限但不算少见。[9]帝国境内的日耳曼语族语言除哥德语外几乎没留下任何文本。[10]多语制使得既非罗马人也非希腊人的少数民族可以通过罗马化或希腊化来构建身份。[11]

古典时代晚期政治权力逐步去中心化后,拉丁语的各种西欧方言逐渐演变为罗曼语族下的各种语言,如西班牙语、葡萄牙语、法语、意大利语、加泰罗尼亚语、奥克语及罗马尼亚语。21世纪初,有超过10亿人的第一或第二语言演化自拉丁语。[12]拉丁语长久以来都是外交和知识传播的重要国际交流媒介,直至现代,法律及罗马天主教教会拉丁语都是如此。

拉丁语

[编辑]

拉丁语有史以来就是罗马人的母语。维吉尔在第一任罗马皇帝奥古斯都统治时期,强调拉丁语是罗马统一和祖宗大法的来源。在维吉尔所作关于罗马的建立的史诗《埃涅阿斯纪》中,主神朱庇特规定,为维持社会统一,来到意大利定居的特洛伊战争难民将使用拉丁人的语言:“他们将保持他们祖先的言辞(sermo)和传统……我将用一种表达方式(uno ore,字面意思“用一张嘴”)使他们都成为拉丁人。”[13]自称是维吉尔笔下英雄埃涅阿斯后裔的儒略-克劳狄王朝皇帝鼓励人民使用高标准的正确拉丁语(Latinitas),即古典拉丁语,且鼓励用拉丁语处理公务。[14]

被征服地区的人民改说拉丁语,使得拉丁语在被征服地区扎根,[15]没有任何法律条文强制推行拉丁语。[16]圣奥古斯丁认为,罗马人喜欢通过社会契约(per pacem societatis)推行拉丁语。[17]这种语言政策与亚历山大大帝的截然相反,他想通过设为官方语言将古希腊语推行至整个帝国。[18]会说拉丁语不是获得罗马公民身份的必要条件,也没有国立学校将其作为教育媒介的特权:流利的拉丁语是因为其“高度的文化、政治、法律、社会和经济价值”才受到青睐的。[19]

拉丁语为帝国工作、晋升所必须,也是政府运作所用的语言。官方通信、跨语言区的法律判决都会使用拉丁语。[20]

罗马人高度重视书面文本,他们高度痴迷于文件与公共碑文的写作。塔木德说:“以海洋为墨,以芦苇为笔,以苍穹为纸,以众生为吏,也写不下罗马政府关注着的全部。”反映了罗马帝国的官僚机构多么依赖于写作。[21]对罗马帝国识字率的估计从5%左右到高于30%,取决于“识字”的定义。[22]国家对受教育机会的干预不足,是识字率提升的一大障碍。正规教育只提供给付得起学费的家庭的孩子。[23]

在亚历山大·塞维鲁(222–235在位)之前,罗马公民的出生证明和遗嘱都必须用拉丁语书写。[25]书记官会给不识字的罗马公民读写官方文书。[26]法律和诏书以书面形式张贴出来,也会有人宣读。[27]公共艺术和宗教仪式是能跨越读写能力的鸿沟,传达帝国意志的方式。[28]希腊盐源将一种早期的叙事芭蕾(pantomimus)带到了罗马,并在整个多语制帝国内流行起来,部分原因是它依赖肢体语言进行表达。[29]

直到6世纪中叶,拉丁语一直罗马军队的官方语言,在东罗马帝国也是最常用的军事语言,直至630年代帝国公用语改为拉丁语为止。[30]相比之下,已知只有两位主教在狄奥多西二世(~450)统治期间举行的大公会议上讲过拉丁语。[31]

希腊语

[编辑]

通俗希腊语在亚历山大大帝征服之后成为了东地中海及小亚细亚地区的通用语。[32]琉善甚至想象希腊语是冥界的通用语。[33]古典时代晚期的希腊语人群主要分布在希腊半岛及爱琴海诸岛、近东大城市及安纳托利亚大部。[34]希腊语在东罗马帝国仍是官方语言,并演变为中古希腊语和现代希腊语。[35]

克劳狄一世试图限制希腊语的使用,有时还取消拉丁语不流利者的公民身份。不过在罗马元老院讲话时,他还是会跟希腊地区的元老讲希腊语。[14]苏埃托尼乌斯引用他的话说“我们的两种语言”,[37]雇佣两名官职相同,而一名说拉丁语、另一名说希腊语的大臣的做法也始见于他在位期间。[38]

两种语言日常的相互渗透体现在双语碑文中,有时甚至在两种语言间来回切换。例如,一个希腊士兵的墓志铭可能主要由希腊语撰写,而他在军中的军衔和作战单位则由拉丁语表达。[39]

东罗马帝国的法律和官文经常要从拉丁语翻译为希腊语。[40]5世纪时政府官员和教会两种语言都会积极使用。[41]自6世纪开始,西方人几乎完全依靠拉丁语翻译来研究希腊文化。[42]拉丁语借词大量出现在古典时代晚期及拜占庭时期技术主题的希腊语文本中。[43]

语言改革运动

[编辑]雅典主义是第二次诡辩运动的趋势之一。埃利乌斯·阿里斯提德斯等知识分子试图恢复以修昔底德、柏拉图、狄摩西尼及其他古典希腊时期学者为代表的阿提卡希腊语。有志于此的散文家试图回避通用希腊语的“粗话”,这虽然螳臂当车,但也反映了2世纪亚历山大语法学派和辞书学的蓬勃发展。[44]语言文学方面的专业知识有助于在罗马世界中保存希腊文化。[45]

戴克里先(284–305在位)试图恢复拉丁语的权威性,希腊语成语ἡ κρατοῦσα διάλεκτος (hē kratousa dialektos)说明拉丁语作为“权力的语言”具有相当的权威性。[46]学者利巴尼乌斯(4世纪)认为拉丁语导致了希腊语修辞质量的下降。[47]在6世纪初,查士丁尼一世试图将拉丁语重新确立为法律用语,但在他的时代,拉丁语在东方已经不再具备什么实用价值。[48]

区域性语言

[编辑]

因为讲拉丁语和希腊语的识字精英中的主导地位,帝国的众多口语的连续性时常会被掩盖,但不能忘记人所有语言交流和大部分的文化活动都会基于口语而运行。[49]科普特语、阿拉姆语、布匿语等语言广泛地分布在被帝国征服的地区当中,并在那里与拉丁语和希腊语共存。[50]

阿拉姆语和叙利亚语

[编辑]阿拉姆语是叙利亚及美索不达米亚地区的主要语言,有几种方言。[34]叙利亚语分布在帝国三大城市之一安条克周边,主要由基督徒使用。[51]叙利亚语文学发端自2世纪后半叶,从埃德萨周边的基督徒社区散播开来。[52]4世纪之前的早期叙利亚语文学诞生在希腊的知识环境中,但其丰富的象征和对格律的重视又使其与众不同,还影响了优西比乌、巴西流及狄奥多勒等希腊学者。[53]已知最早的叙利亚语著作包括他提安《四福音合参》及《圣经》中的部分译文。[52]

多产的叙利亚学者巴代珊通晓希腊语,并送他的儿子去雅典上学,但用自己的母语写作。除了说教作品、专题文章之外,巴代珊还写了150首“影响巨大、教义可疑”的赞美诗。[54]这一时期其他叙利亚语文学作品还有基督教论文、对话录及使徒传记。[52]一些作品包含诺斯底主义元素,在摩尼教的传播中也发挥了作用。5世纪之后,基督一性论和聂斯托里主义著作也被包括进来。[55]

叙利亚学者圣耶福列木的著作后来被翻译为希腊语。[56]讽刺作家、修辞学家琉善来自叙利亚萨摩萨特;虽然他以希腊语写作,但他自称是叙利亚人,还说自己是“蛮族”,说明他自己的母语可能是叙利亚语。[57]

来自巴尔米拉的士兵甚至在碑文上也用巴尔米拉阿拉姆语来写作。[58]

科普特语

[编辑]

“科普特语”实际上指的是现代埃及语。[59]书面科普特语似乎是埃及教育阶层有意识地恢复其文化的结果。[60]

科普特文基于希腊字母,额外加上来自世俗体的少数反映埃及语语音的字符。古孟斐斯方言、法尤姆方言、艾赫米姆方言、沙希地方言在4世纪时曾用这种科普特文记录。[60]这一时期,科普特语衍生出一套完整的书面标准,包括对希腊语经文、礼仪文本和教父学著作的翻译。[61]4至7世纪,颂歌、圣徒传记、修行规矩、书信、建议信等的原始文本都是用科普特语创作的,主要用的是沙希地方言。[62]书面科普特语用于清单、地产交易等日常用途以及诗歌中。[63]至640年代穆斯林征服埃及,科普特基督徒尚占人口的大多数。[64]到7世纪末,法律文本可能仍用科普特语书写。例如,一份提及穆罕默德的希腊-阿拉伯语双语外交规章,其后跟着一份科普特语文本,其中提到了三位一体。[64]

布匿语

[编辑]布匿语是古迦太基所用的闪米特语族语言,在罗马帝国统治期间也在北非通行。[65]在公元前146年被罗马征服之前,所有布匿语铭文都是对塔尼特和巴力等神的祭祀或墓志。而在罗马治下,新布匿语的语料丰富得多,往往与拉丁语或希腊语的对应同时出现。[66]在大莱普提斯建于公元14–19年之间的罗马女神和奥古斯都神庙中,发现了引人注目的新布匿语铭文。[67]纪念碑上最晚的新布匿语铭文刻于图密善在位期间(81–96在位)。[68]石刻布匿语铭文无一晚于2、3世纪。[69]4、5世纪有用拉丁字母书写布匿语的例子。[70]

布匿语由社会精英使用:塞普蒂米乌斯·塞维鲁(193–211在位)生在大莱普提斯,通晓布匿语、拉丁语、希腊语,而他的妹妹据说压根不懂拉丁语。[71]北非的奥古斯丁多次提到布匿语:他观察到它与希伯来语、叙利亚语有关。他对布匿语的了解帮他从《圣经》中找出音译的闪米特语单词。ref>Jongeling and Kerr, Late Punic Epigraphy, p. 4.</ref>

凯尔特语

[编辑]凯尔特语族在公元初年包括高卢省(今日法国、比利时、瑞士及意大利北部)的高卢语、西班牙省(西班牙与葡萄牙)的凯尔特伊比利亚语和加利西亚语、古布立吞语(不列颠尼亚省)及公元前3世纪由一支凯尔特人带到安纳托利亚的加拉提亚语。地名加拉太(Galatia)来自希腊语中表示“高卢人或凯尔特人”的词Galatai。拉丁语中的高卢语借词可以追溯到昆图斯·恩纽斯(239–169 BC),由于意大利半岛上有凯尔特人定居点,拉丁语中开始出现高卢语的借词。[72]到古典时代晚期,一些高卢词已经拉丁化到人们不再承认其来源了。[73]

公元前2世纪与罗马人接触后,凯尔特伊比利亚语才有书面记录。[74]所有103块现存凯尔特伊比利亚语铭文中,有30块用伊比利亚文字写的,是招待用的信物(tesserae hospitales),其中20块外形类似于动物。[75]家庭或社区之间承诺相互支持的社会习俗同罗马文化中的主客关系类似。被罗马征服后,凯尔特伊比利亚人改用拉丁语制作这种信物,直到2世纪。[76]奥古斯都时期,凯尔特伊比利亚人的领土成为了塔拉科西班牙的一部分。[77]书面凯尔特伊比利亚语在奥古斯都时代之初就消失了。[78]

古典时代晚期有些史料提及了高卢语,说明它可能还有人使用。177年,卢格度努姆(今日的莱昂)主教爱任纽抱怨说,他不得不用那种“蛮子话”(可能是高卢语)跟教区居民交流。[79]法学家乌尔比安(170–228)提到了要识别高卢语口语。[80]埃利乌斯·兰普雷底斯说,一名女德鲁伊用高卢语对亚历山大·塞维鲁(208–235)做出了预言。[81]耶柔米(331–420)拥有第一手资料,他认为高卢特雷维里人的语言与加拉太的“差不多”。[82]波尔多的马塞勒斯(4世纪末至5世纪初)的药方集包含一些高卢语词汇,主要是植物名,似乎表明高卢语在传统医学或魔法等领域仍在使用。[83]同样来自阿基坦高卢的苏尔皮基乌斯·塞维鲁斯(363–425)注意到了高卢语和拉丁语的双语,其中高卢语是“母语”。其他提到“以高卢语方式”(gallice)或类似方式说话的人可能是指说高卢口音的拉丁语。[81]

许多历史语言学家认为,高卢语在6世纪中后期在法国应仍有使用。[84]尽管当地物质文化被大规模罗马化,但高卢语在整个罗马统治期间一直存活,并与拉丁语口语共存。[84]

日耳曼语

[编辑]日耳曼语族中只有哥特语有零星记载。《拉丁语选集(Latin Anthology)》所载一副挽联中引用了哥特语短语,[85]福音书的主体被翻译为哥特语,既是6世纪的“银圣经”。[10]拉丁语中含有少量日耳曼语借词,而日耳曼语对拉丁语的影响更多的不在词汇上。[86]

日耳曼-拉丁语双语制在日耳曼人占多数的军队中对于军官来说尤为重要。塔西佗注意到,战胜了罗马军队的切鲁西人军官阿米尼乌斯就是个双语者。[87]皇帝尤利安雇了一名会说日耳曼语的军事保民官为间谍。[88]军官和将文书记在文德兰达石板上的秘书是巴达维人,但他们的拉丁文中没有任何提示;他们手下的普通士兵可能还只说日耳曼语。[89]拉丁人军官在部队中学会一种日耳曼语并充当翻译的情况并不多见。[90]学会一门日耳曼语是一种令人起疑的成就,会引起对“野蛮”的焦虑:在5世纪的高卢,圣希多尼乌斯·阿波利纳里斯觉得自己博学的朋友夏克立乌斯精通日耳曼语十分有趣。[91]

多语

[编辑]三语在来自非拉丁语或希腊语区的受教育人群中并不多见。拉丁小说家阿普列尤斯也以希腊语写作,还从母亲那学会了布匿语。[92]《芭芭沙档案(Babatha Archive)》是多语制存在的有力证据,这些莎草纸文稿创作于公元93至132年间,以佩特拉阿拉伯一名犹太女性的名字命名,主要以当地语言阿拉姆语写就,所用文字则为受到闪米特语族和拉丁语影响的希腊字母;一份交给罗马总督的申请书则以希腊语写成。[93]

罗马帝国多语多文化的一个典型例子是一块刻于2世纪的名为Regina的女性的墓志铭,1878年出土于英格兰东北部南希尔兹附近的罗马据点遗址。铭文主要由拉丁语和帕尔迈拉文阿拉米语写就,后者是Regina之夫Barates的母语,叙利亚帕尔迈拉出土的碑文称他是旗手。[94]他参与戍守哈德良长城一带的军队。拉丁语则在语法上同帕尔迈拉的希腊语敬辞铭文相仿,说明Barates是个会说阿拉姆语和希腊语的双语者,且拉丁语是他的第三语言。拉丁语所占部分更大,篇幅也更长,涵盖了主要的信息。帕尔迈拉文为一种十分流畅的手写体,用这种文字刻写的部分只涉及Regina的名字,以及对她逝世的悼念悲痛之情。不列颠岛上能阅读这种文字的人显然很少,因而Barates大概用它来表达自己的个性及情感。Regina这个名字既可能是拉丁语名字,也可能是凯尔特语名字。人们似乎因为这种二元性,格外偏爱这种名字。Regina自认为是不列颠卡图维勒尼人(Catuvellauni),其首都或说主要居民点是维鲁拉米恩,但在拉丁文碑文中用的,则是高卢-布立吞拼法Catuallauna(阴性)。[95]

地理分布

[编辑]意大利半岛与西西里

[编辑]在意大利,拉丁语到1世纪末在书面上渐渐取代了奥斯坎语和伊特拉斯坎语。[96]位于奥斯坎语区的庞贝和赫库兰尼姆古城的奥斯坎语涂鸦被79年维苏威火山爆发保存下来。少数涂鸦的年代可能在62年庞贝地震前后。[97]在1世纪中叶,钟意于古玩的克劳狄一世了解到了伊特拉斯坎语,并为伊特拉斯坎人撰写了一部多卷史书,但现已失传。[98]

西西里行省的多语制曾持续了数个世纪,是先后受迦太基人、希腊人、罗马人统治的结果。罗马共和国期间的奴隶贸易将讲希腊语及其他语言的人从东方带来西西里,后来在罗马帝国时期,希腊语成为了官员和商人等社会地位更高的人的通用语。[99]帝制时代早期向西西里的移民说拉丁语的更多。非洲裔拉丁语使用者在西西里举足轻重。[100]基督教铭文更有可能是希腊语写的。[101]在古典时代晚期,希腊-拉丁语双语已经足够普遍,甚至在日常人际交流中扎根下来。[102]锡拉库萨的犹太人社区似乎是希腊-希伯来语双语的。[103]西西里岛上也有些叙利亚语的考古证据。[103]

西部省份

[编辑]

在罗马帝国西部,拉丁语逐渐取代了凯尔特诸语。句法和词汇上的共性促进了向拉丁语的转变。[104]纳博讷高卢(法国南部)在公元前1世纪中叶甚至三语并行(希腊语、拉丁语、高卢语)。[105]拉丁语在提供接触统治权力结构的机会上十分重要,使得伊比利亚半岛(西班牙省)和高卢的当地语言快速灭绝。独立的高卢-罗马文化可能创造了高卢-拉丁文本。[106]在拉丁文墓志铭中,起了凯尔特名字的很少自认为是“凯尔特人”或“高卢人”;他们更可能自称有公民证的部落,如爱杜依人、雷米人、皮克通人,[107]或有投票权的部族。帝制时代有些大学者出身于伊比利亚半岛,如塞内卡、卢坎、昆提利安、[108]马提亚尔及普鲁登修斯。虽然当地有很多罗马化的文物,不过高卢语坚持了相当长的时间,可能直到6世纪中叶。[84]

纳博讷高卢136块希腊语铭文中的大部分,包括原来来自希腊殖民地的,年代都晚于奥古斯都时期。[109]其内容表明,希腊语存在用于特殊用途的趋势:“教育、医疗、戏剧、不可知论活动、艺术、魔法、宗教,其中包括基督教”。[110]位于今日马赛的希腊殖民地福西亚建立于约公元前600年,出土的铭文表明到公元2、3世纪希腊语仍用在教育和医疗领域。[111]出身阿基坦高卢(今日波尔多)的拉丁诗人、学者马格努斯·奥索尼乌斯(4世纪)将他的父亲描述为一个雅典话比拉丁语还流畅的医师。[112]

巴斯克语不是印欧语,分布在比利牛斯山中的小片区域。[113]凯撒认为高卢西南部和西班牙东北部(大致对应今日阿基坦和纳瓦拉)的居民不属于凯尔特人;从地名可以看出,他们使用的阿基坦语同巴斯克语一样属于瓦斯科尼亚语系。阿基坦人在罗马统治时期接受了拉丁语。[114]

高卢语在高卢一直存续到6世纪末,在高卢-罗曼语支的谱系划分中起着重要作用。[84]拉丁语在不列颠尼亚省的影响力相对较弱,在410年左右罗马人撤退之后可能就迅速衰亡了,不过不列颠西部小块的拉丁语语言岛可能一直存续到8世纪。[115][108]古布立吞语中的拉丁语借词表明,不列颠尼亚省的拉丁语偏向于学术方面,与欧洲大陆上的“通俗拉丁语”不同。[116]

非洲省份

[编辑]

在昔兰尼加(自公元前7世纪起被希腊人殖民)以西的阿非利加省,迦太基人和其它腓尼基殖民地的居民会读写布匿语,而拉丁语在市中心更常用。其他地区的人多说亚非语系语言(如利比亚语、努米底亚语),可能后来演变为柏柏尔语族。[117]

布匿语曾用于提贝里乌斯(1世纪)时期硬币上的铭文,还出现在2世纪的一些公共建筑上,有的是与拉丁语构成的双语铭文。[106]甚至有三语铭文:一份与帝国崇拜有关的写道“官用拉丁语,土用布匿语,商、教、精英用希腊语”。[118]

利比亚语铭文所用的文字与提非纳文字十分相似,一般从下往上写。23种字符的“形体相当地僵硬”。[119]与布匿语、与拉丁语构成双语铭文的均有见,说明能书写这些语言的人也能用利比亚文转写自己的名字。利比亚文铭文聚集在希波城东南,紧邻今日阿尔及利亚-突尼斯国境,其分布表明关于利比亚语的知识不限于那些孤立的社区。[120]

帝制时代出身于非洲的著名拉丁学者有小说家阿普列尤斯、特土良、奥古斯丁等教父。汪达尔-阿兰王国(435–534)期间,北非留有一些拉丁语社区,特别是在迦太基附近。但它们到7世纪晚期,随着阿拉伯人的征服也都消亡了。[108]

罗杰·布伦奇(2018)[121]认为,虽然柏柏尔语支几千年前就从亚非语系中分离出来,原始柏柏尔语的年代却只可能上推到公元200年之迟,因为现代柏柏尔语言的多样性相当之低。原始柏柏尔语中的布匿语借词表明,现代柏柏尔语的分化大抵起源自公元前146年古迦太基的陷落;关切语和塞那加语缺乏布匿语借词。[121]另外,原始柏柏尔语中的拉丁语借词也表明,原始柏柏尔语的分化大概在公元1或2世纪。在罗马帝国时期,牛耕、骆驼、果园管理等罗马人的发明被罗马帝国界墙沿线的柏柏尔部落借鉴而去,创造出一种新兴的贸易文化及一种新的通用语,后者也就是原始柏柏尔语的前身。[121]

埃及

[编辑]

埃及主要说科普特语,[122]自亚历山大征服以来也通行希腊语,罗马帝制时代拉丁语和希腊语是主要的行政用语。[123]建城于公元前331年的亚历山卓是罗马帝国最大的三座城市之一,无论希腊时代还是罗马时代都是希腊文化的“理性生活之都”。亚历山大图书馆闻名遐迩,也是基督教传教的中心之一。埃及的希腊语使用者是第一批皈依基督教的。[124]

进入8世纪,希腊语的地位被征服者阿拉伯语所取代。科普特语也开始衰落,自此之后,主要用于宗教仪式。[60]

东部

[编辑]虽然希腊语的使用环绕地中海、深入小亚细亚直至边境之外,但罗马帝国东部的语言分布状况十分复杂。安纳托利亚的现已绝迹语言有加拉提亚语(公元前3世纪驻扎小亚细亚的高卢军队的凯尔特语后裔)、弗里吉亚语、皮西迪亚语及古卡帕多西亚语,均可见于帝制时代的铭文。[125]基督教文献也提到了小亚细亚的加拉提亚语、卡帕多西亚语、密细亚语及伊苏利亚语。[126]它们均属于印欧语系。弗里吉亚语直到6世纪都不被看做是一种语言,但保留在了上百块希腊文墓志铭中,大多伴有希腊语文本,年代基本都在3世纪之后。[126]似乎有少数文献提到了希腊语的卡帕多西亚口音。[127]

在军队之外,拉丁语只在贝利图斯(今日贝鲁特)等罗马殖民地成为帝国东部日常交流的用语。这些殖民地仍有拉丁语教育,并以罗马法贝利图斯学派而闻名。[128]

多瑙河省份及巴尔干半岛

[编辑]多瑙河诸省指的是多瑙河中下游盆地、东阿尔卑斯山脉、迪纳拉山脉及巴尔干山脉一带的罗马行省,主要有诺里库姆、达契亚、达尔马提亚、默西亚、色雷斯、小斯基提亚、潘诺尼亚等行省。[129] 拉丁语和希腊语影响的孰多孰寡可以划出界来,也称伊雷切克线。

希腊语自从公元前4世纪末以来就是巴尔干半岛南部的通用语,这是腓力二世和亚历山大征服的影响。古马其顿语可能是一种希腊语方言,[130]当时大约分布在今日的马其顿与希腊北部;此区域以北,则是培奥尼亚语;偏南的伊庇鲁斯地区则可能是双语地区。[131]

伊利里亚语分布在西北部,色雷斯语和达契亚语则分布在东北部。[131]这三种印欧语都有可能是阿尔巴尼亚语的祖先。[131]奥古斯特时代诗人奥维德在流亡到黑海旁的托米斯(今日罗马尼亚康斯坦察)学会了盖塔语(达契亚语)和斯基泰语,并指出当地的希腊语有很重的盖塔口音。[132]托米斯出土的罗马帝国时代铭文一般都用希腊语书写,带些色雷斯语人名和宗教影响。[126]

犹太大流散

[编辑]

犹太人刻凿的希腊语和拉丁语铭文说明了犹太人被迫接纳多语,他们在帝国内的分布反映了犹太人流散。[133]这种碑文在结尾一般都有希伯来语祝词“舍拉姆”(意为“平安”)。[134]可见于莎草纸的埃及犹太人存在证据在116–117年的叛乱之后不复存在。[135]在5世纪上半叶,希腊语、希伯来语和犹太-阿拉姆诸语在第一巴勒斯坦省和第二巴勒斯坦省的犹太人社区共存,甚至在犹太教堂的马赛克铭文中也能观察到。[50]

同七十士译本类似,罗马帝国时代之前的希伯来圣经希腊语译本,以及罗马帝国时代的希腊语犹太教经典主要写给说希腊语的犹太人。[136]有些犹太人在希腊时代末、罗马时代初会写希腊语—比较有名的是哲学家斐洛和历史学家弗拉维奥·约瑟夫斯—他们的目标受众中也包括非犹太人。[137]西比拉神谕和所罗门智训是这一时期希腊语写的犹太教经典的典型例子。[138]

作于公元100年以后的现存希腊语文献的作者没有一人能确定是犹太人。这之后,希腊语写的犹太文化作品与基督教渐渐疏离了。中世纪犹太文化的手稿传统仅保存于希伯来语和阿拉姆语文献。[139]

基督教社区

[编辑]《丢格那妥书》称,语言不是决定基督教教徒身份的因素;基督教教徒可以说任何语言。[140]到古典时代晚期,至少部分基督教文学作品出现了帝国通行的各语言的不同版本。[141]

希腊语的国际化使用是基督教得以广泛传播的因素之一,如保罗书信用的就是希腊语。[6]第一个积极推广基督教的罗马皇帝君士坦丁一世大概会讲一些希腊语,但朝廷上则只说拉丁语,在第一次尼西亚公会议上还雇了翻译来跟说希腊语的主教交流。[143]在帝国西部、西罗马帝国,希腊语则被认为是一种外语。[144]圣奥古斯丁坦白,他讨厌希腊语,觉得它很难学。[145]不过到古典时代晚期,讲希腊语不再被认为是一种牵涉希腊人宗教文化的事了。[146]在5世纪上半叶,希腊语是主教们交流所用的标准用语,[147]Acta Conciliorum(“大公会议法令”)也以希腊语记录,之后才翻译成拉丁语、叙利亚语、科普特语。[148]这一时期,拉丁语只在大公会议中起次要作用,西方帝国的代表也是如此。[149]尽管传统上一般认为,到这一时期亚美尼亚语也被认为是一种基督教语言,但它并不出现在“法令”中。[150]有证据表明会上也有人说科普特语,但内容没有被记录下来。[151]其他语言可以被现场翻译为希腊语,包括“阿拉伯人”“撒拉森人”“以实玛利人”所说的语言。[152]基督教相关的文本在6世纪也零星见于一些阿拉伯语铭文。[152]

仪式(巫术)用语

[编辑]被称为“巫术”或说“魔法”[153]的私人化仪式所用的语言可能是大杂烩。巫术以及一些药方几乎总是包括咒语的诵读,往往伴随着护身符、刻字板的创作。这些有考古证据和文献支持,如可追溯到公元前2世纪到公元5世纪的希腊巫术莎草纸,就是一套咒语集。尽管奥古斯都试图通过烧掉两千本上下的魔法书来遏制巫术发展,[154]巫术还是在整个帝国流传开来,并证实了帝国人民对多语言的认识。[155]咒语未经翻译,因为其法力被认为寄寓在具体的发音当中;[156]因此高卢语等语言可能在这种私人仪式中存活了相当久。[157]

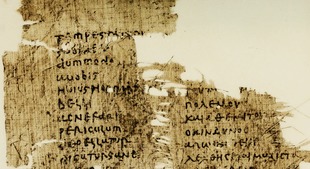

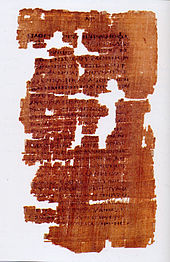

希腊巫术莎草纸反映了希腊-埃及文化的交融,不只局限在古埃及宗教和古希腊宗教方面,还有犹太教巫术及少量基督教魔法等近东元素。埃及和希腊神明、犹太教神明和天使、耶稣的名字都有所反映。希腊巫术莎草纸主要用希腊语写成,也有不少段落用的是世俗体[158],还塞入了不少“能读但读不懂”的音节。[159]这些咒语遍及巫术文献及铭文,[160]常常掺杂科普特语、[161]希伯来语、[162]阿拉姆语或其他闪米特语[163]及凯尔特语的词汇。[164]希伯来语和希腊语出现在世俗魔法书中;科普特巫术吸收了一些希伯来语;拉丁语咒语中冒出埃及话。[165]许多咒语可能蓄意地造出了新词或愚民的效果,[166]学者们认为,理论上更多可释读的段落可能是在抄录原文或转述口语时出现的误解的结果。[167]

高卢的巫术实践碑文显示了罗马帝国时期使用希腊语施法的特点。欧坦出土的一张2世纪咒符用拉丁语列出了被诅咒者的名字,用希腊语列出了一系列咒语。[168]阿梅利莱班-帕拉尔达出土的一张咒符似乎是凯尔特语和拉丁语交杂而成的。[169]出土于不列颠尼亚省的一张咒符上有用希腊文写的希伯来语咒语。[170]

晚期古典时代的基督教可能会在希腊语驱魔咒语中插入希伯来语。[171]圣耶柔米报告过一个奇怪的故事:一个只会古法兰克语和拉丁语的皇家卫队士兵,在被附身时开始说流利的阿拉姆语。[172]

法律用语

[编辑]罗马法是用拉丁文写成的,“法律条文”与它所表达的文字严格挂钩。[173]然而任何语言都可以在更普遍的口头契约和基于《万民法》或国际法的程序中具有其约束力。[174]《万民法》不是一部书面法律规范,而是作为一种自然法,存在于所有民族之间。罗马法学家为确保人民对法律条文的正确理解,对地方语言,如布匿语、高卢语和阿拉姆语表达了高度关切。[122]

虽然直到220年代,罗马公民的出生证和遗嘱都必须用拉丁文书写,[25]但在乌尔比安的法律意见书(ca. 215)中,委托遗赠(信托方式的遗赠[175])就不限于拉丁语或希腊语,也可以用“布匿语、高卢语或任何其他”语源订立。[176]最初,遗嘱人的委托遗赠将继承者置于道德而非法律义务下,[177]而乌尔比安断言“任何语言都包含其言语的义务,只要各方能通过自己的母语或准确的翻译理解对方的意思”。[178]法学家盖约区分了口头契约和义务,前者的效力来自拉丁语的公式化言语,而后者则表达了对《万民法》的相互理解,无论双方是否是罗马人。[179]

语言遗留

[编辑]

在古典时代晚期政治权力的去中心化之后,拉丁语依地域逐渐演变为罗曼语族各语言,主要有西班牙语、葡萄牙语、法语、意大利语、罗马尼亚语、加泰罗尼亚语、撒丁语、阿罗马尼亚语、非洲罗曼语、莫扎拉布语、达尔马提亚语及威尼托语,还有些别的语言。拉丁语作为一种用于书面的国际语言,继续充当着外交、教育的重要媒介,直到17世纪的文艺复兴人文主义、至今的法律及罗马天主教教堂中发挥着重要作用。[180]

希腊语则为拜占庭帝国所继承,但从未替代与其共存的任何语言,如埃及的科普特语或中东的阿拉姆语。[181]

参考

[编辑]- ^ Richard Brilliant, "Scenic Representations," in Age of Spirituality: Late Antique and Early Christian Art, Third to Seventh Century (Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1979), pp. 96–97.

- ^ Bruno Rochette, "Language Policies in the Roman Republic and Empire," translated by James Clackson, in A Companion to the Latin Language (Blackwell, 2011), p. 560.

- ^ Alex Mullen, "Introduction: Multiple Languages, Multiple Identities," in Multilingualism in the Graeco-Roman Worlds (Cambridge University Press, 2012), p. 28.

- ^ Rochette, "Language Policies in the Roman Republic and Empire," pp. 554, 556.

- ^ J.N. Adams, "Romanitas and the Latin Language," Classical Quarterly 53.1 (2003), pp. 185–186, 205.

- ^ 6.0 6.1 Treadgold, A History of the Byzantine State, p. 5.

- ^ The Oxford Handbook of the Literatures of the Roman Empire (页面存档备份,存于互联网档案馆), edited by Daniel L. Selden and Phiroze Vasunia (Oxford University Press). Richard Valantasis, introduction to Religions of Late Antiquity in Practice (Princeton University Press, 2000), p. 11.

- ^ MacMullen, "Provincial Languages in the Roman Empire," pp. 15–16.

- ^ Joseph Eska, "Inscriptions in the Celtic World," in Celtic Culture: A Historical Encyclopedia (ABC-Clio, 2006), pp. 965–970.

- ^ 10.0 10.1 Tore Janson, A Natural History of Latin (Oxford University Press, 2004), p. 87.

- ^ Mullen, Southern Gaul and the Mediterranean, pp. 264–265.

- ^ James Clackson, introduction to A Companion to the Latin Language, p. 1.

- ^ Virgil, Aeneid 12.834 and 837; Rochette, "Language Policies in the Roman Republic and Empire," pp. 549, 563; Adams, "Romanitas and the Latin Language," p. 184.

- ^ 14.0 14.1 Rochette, "Language Policies in the Roman Republic and Empire," p. 552.

- ^ József Herman, Vulgar Latin, translated by Roger Wright (Pennsylvania State University Press, 2000, originally published 1975 in French), p. 10.

- ^ Rochette, "Language Policies in the Roman Republic and Empire," p. 549; Charles Freeman, The Greek Achievement: The Foundation of the Western World (New York: Penguin, 1999), pp. 389–433.

- ^ Augustine of Hippo, De Civitate Dei 19.7.18, as cited by Rochette, "Language Policies in the Roman Republic and Empire," p. 549.

- ^ Rochette, "Language Policies in the Roman Republic and Empire," p. 549, citing Plutarch, Life of Alexander 47.6.

- ^ Mullen, Southern Gaul and the Mediterranean, p. 265.

- ^ Millar, A Greek Roman Empire, p. 92.

- ^ Clifford Ando, Imperial Ideology and Provincial Loyalty in the Roman Empire (University of California Press, 2000), pp. 86–87.

- ^ William V. Harris, Ancient Literacy (Harvard University Press, 1989), p. 5; William A. Johnson, Ancient Literacies: The Culture of Reading in Greece and Rome (Oxford University Press, 2009), pp. 3–4, especially note 5; T.J. Kraus, "(Il)literacy in Non-Literary Papyri from Graeco-Roman Egypt: Further Aspects of the Educational Ideal in Ancient Literary Sources and Modern Times," Mnemosyme 53.3 (2000), p. 325; Marietta Horster, "Primary Education," in The Oxford Handbook of Social Relations in the Roman World, pp. 89, 97–98.

- ^ Christian Laes, Children in the Roman Empire: Outsiders Within (Cambridge University Press, 2011, originally published in Dutch 2006), p. 108; Horster, "Primary Education," in The Oxford Handbook of Social Relations in the Roman World, p. 89.

- ^ IG 14.1125

- ^ 25.0 25.1 Adams, "Romanitas and the Latin Language," pp. 186–187.

- ^ Ando, Imperial Ideology and Provincial Loyalty in the Roman Empire, p. 101; Kraus, "(Il)literacy in Non-Literary Papyri from Graeco-Roman Egypt," pp. 325–327.

- ^ Susan P. Mattern, Rome and the Enemy: Imperial Strategy in the Principate (University of California Press, 1999), p. 197; Teresa Morgan, Literate Education in the Hellenistic and Roman Worlds (Cambridge University Press, 1998, 2000), pp. 1–2 et passim; Greg Woolf, "Literacy or Literacies in Rome?" in Ancient Literacies, p. 46ff.; Horster, "Primary Education," in The Oxford Handbook of Social Relations in the Roman World, p. 97. Ando poses the question as "what good would 'posted edicts' do in a world of low literacy?' in Imperial Ideology and Provincial Loyalty in the Roman Empire, p. 101.

- ^ Ando, Imperial Ideology and Provincial Loyalty in the Roman Empire, pp. 152, 210.

- ^ Edith Hall, introduction to New Directions in Ancient Pantomime (Oxford University Press, 2008), pp. 6–7.

- ^ Rance, "The De Militari Scientia or Müller Fragment," pp. 63–64.

- ^ Millar, A Greek Roman Empire, p. 100.

- ^ Millar, A Greek Roman Empire, p. 279; Treadgold, A History of the Byzantine State and Society, p. 5.

- ^ Lucian, Dialogue of the Dead 25; Anderson, The Second Sophistic, p. 194.

- ^ 34.0 34.1 Treadgold, A History of the Byzantine State and Society, p. 5.

- ^ Stefan Zimmer, "Indo-European," in Celtic Culture: An Historical Encyclopedia, p. 961.

- ^ Cicero, In Catilinam 2.15, P.Ryl. I 61 "recto".

- ^ Suetonius, Life of Claudius 42.

- ^ Rochette, "Language Policies in the Roman Republic and Empire," p. 553; Lee I. Levine, Jerusalem: Portrait of the City in the Second Temple Period (538 B.C.E. – 70 C.E.) (Jewish Publication Society, 2002), p. 154.

- ^ Rochette, "Language Policies in the Roman Republic and Empire," p. 556; Adams, "Romanitas and the Latin Language," p. 200.

- ^ Rochette, "Language Policies in the Roman Republic and Empire," pp. 553–554.

- ^ Millar, A Greek Roman Empire, pp. 93¬94.

- ^ Moatii, "Translation, Migration, and Communication," p. 112.

- ^ Rance, "The De Militari Scientia or Müller Fragment," p. 63.

- ^ Anderson, The Second Sophistic, pp. 87–91.

- ^ Anderson, The Second Sophistic, p. 101.

- ^ Rochette, "Language Policies in the Roman Republic and Empire," p. 560.

- ^ Rochette, "Language Policies in the Roman Republic and Empire," p. 560; A.H.M. Jones, The Decline of the Ancient World (Longmanns, 1966), p. 346.

- ^ Rochette, "Language Policies in the Roman Republic and Empire," pp. 562–563.

- ^ Richard Miles, "Communicating Culture, Identity, and Power," in Experiencing Rome: Culture, Identity and Power in the Roman Empire (Routledge, 2000), pp. 59–60.

- ^ 50.0 50.1 Millar, A Greek Roman Empire, p. 95.

- ^ MacMullen, "Provincial Languages," p. 4.

- ^ 52.0 52.1 52.2 MacMullen, "Provincial Languages," p. 5.

- ^ MacMullen, "Provincial Languages," p. 6.

- ^ MacMullen, "Provincial Languages," pp. 4–5.

- ^ MacMullen, "Provincial Languages," pp. 5–6.

- ^ MacMullen, "Provincial Languages," p. 7.

- ^ Edwards et al., introduction to Apologetics in the Roman Empire, p. 7; Matthew W. Dickie, "Lucian's Gods: Lucian's Understanding of the Divine," in The Gods of Ancient Greece: Identifies and Transformations (Edinburgh University Press, 2010), p. 350.

- ^ Adams, "Romanitas and the Latin Language," p. 199.

- ^ Mark Sheridan, From the Nile to the Rhone and Beyond: Studies in Early Monastic Literature and Scriptural Interpretation (Studia Anselmiana, 2012), p. 225.

- ^ 60.0 60.1 60.2 Sheridan, From the Nile to the Rhone, p. 226.

- ^ Maged S.A. Mikhail, "An Historical Definition for the 'Coptic Period'," in Coptic Studies on the Threshold of a New Millennium. Proceedings of the Seventh International Congress of Coptic Studies Leiden 2000 (Peeters, 2004), vol. 2, p. 972.

- ^ Mikhail, "An Historical Definition for the 'Coptic Period'," p. 973; Sheridan, From the Nile to the Rhone, p. 226.

- ^ Mikhail, "An Historical Definition for the 'Coptic Period'," p. 973.

- ^ 64.0 64.1 Mikhail, "An Historical Definition for the 'Coptic Period'," p. 974.

- ^ Adams, Bilingualism and the Latin Language, pp. 201, 213.

- ^ Andrew Wilson, "Neo-Punic and Latin Inscriptions in Roman North Africa: Function and Display," in Multilingualism in the Graeco-Roman Worlds, pp. 266–268.

- ^ Wilson, "Neo-Punic and Latin Inscriptions in Roman North Africa," p. 282.

- ^ Wilson, "Neo-Punic and Latin Inscriptions in Roman North Africa," p. 295.

- ^ Wilson, "Neo-Punic and Latin Inscriptions in Roman North Africa," p. 269.

- ^ Wilson, "Neo-Punic and Latin Inscriptions in Roman North Africa," p. 307ff.

- ^ Karel Jongeling and Robert M. Kerr, Late Punic Epigraphy (Mohr Siebeck, 2005), p. 4; Wilson, "Neo-Punic and Latin Inscriptions in Roman North Africa," p. 305.

- ^ Adams, Bilingualism and the Latin Language, p. 185 et passim.

- ^ Adams, Bilingualism and the Latin Language, p. 195.

- ^ Fiona A. Rose, "Text and Image in Celtiberia: The Adoption and Adaptation of Written Language into Indigenous Visual Vocabulary," Oxford Journal of Archaeology 22.2 (2003), p. 155.

- ^ Rose, "Text and Image in Celtiberia," pp. 157, 159.

- ^ Rose, "Text and Image in Celtiberia," p. 159; Leonard A. Curchin, The Romanization of Central Spain: Complexity, Diversity and Change in a Provincial Hinterland (Routledge, 2004), p. 120.

- ^ Rose, "Text and Image in Celtiberia," p. 156.

- ^ Adams, Bilingualism and the Latin Language, p. 280.

- ^ Irenaeus, Against Heresies I, preface; Pierre-Yves Lambert, La langue gauloise: description linguistique, commentaire d'inscriptions choisies (Editions Errance, 2003), p. 10.

- ^ Digest 31.1.11; Lambert, La langue gauloise, p. 10.

- ^ 81.0 81.1 Lambert, La langue gauloise, p. 10.

- ^ Jerome, commentary on the Letter to the Galatians; Lambert, La langue gauloise, p. 10.

- ^ Adams, Bilingualism and the Latin Language, p. 192.

- ^ 84.0 84.1 84.2 84.3 Laurence Hélix. Histoire de la langue française. Ellipses Edition Marketing S.A. : 7. ISBN 978-2-7298-6470-5.

高卢语的衰落和消失不仅可以用具体的文化习俗来解释:当凯撒领导着罗马人在公元前1世纪入侵高卢时,高卢逐渐变得深刻地罗马化。在将近500年的时间里,即著名的高卢-罗马时期,高卢语和拉丁语共存;甚至在6世纪,图尔的格雷戈里的证词也证明了高卢语的存在。

- ^ Latin Anthology 285 (= 279 in the edition of Shackleton Bailey): Inter 'eils' Goticum 'scapia matzia ia drincan' / non audet quisquam dignos edicere versus ;Adams, Bilingualism and the Latin Language, p. 275.

- ^ Adams, Bilingualism and the Latin Language, p. 274.

- ^ Adams, Bilingualism and the Latin Language, pp. 274–275, citing Tacitus, Annales 2.10.3.

- ^ Ammianus Marcellinus 18.2.2; Adams, Bilingualism and the Latin Language, p. 275.

- ^ Adams, Bilingualism and the Latin Language, p. 276.

- ^ Adams, Bilingualism and the Latin Language, pp. 276–277.

- ^ Sidonius, Epistle 5.5; Adams, Bilingualism and the Latin Language, p. 277.

- ^ Moatti, "Translation, Migration, and Communication," p. 111, note 9.

- ^ Rochette, "Language Policies in the Roman Republic and Empire," pp. 553–555.

- ^ The second inscription comes from Corstopitum (Corbridge), about 50 kilometers away.

- ^ Mullen, introduction to Multilingualism in the Graeco-Roman Worlds pp. 1–4.

- ^ Miles, "Communicating Culture, Identity, and Power," p. 58.

- ^ James Clackson and Geoffrey Horrocks, The Blackwell History of the Latin Language (Wiley-Blackwell, 2010), p. 83; Herman, Vulgar Latin, p. 11.

- ^ Giuliano Bonfante and Larissa Bonfante, The Etruscan Language (Manchester University Press, rev. ed. 2002), p. 33.

- ^ Kalle Korhonen, "Sicily in the Roman Imperial Period," in Language and Linguistic Contact in Ancient Sicily (Cambridge University Press, 2012), p. 332.

- ^ Korhonen, "Sicily in the Roman Imperial Period," pp. 336–338.

- ^ Korhonen, "Sicily in the Roman Imperial Period," 339–340.

- ^ Korhonen, "Sicily in the Roman Imperial Period," p. 363.

- ^ 103.0 103.1 Korhonen, "Sicily in the Roman Imperial Period," p. 366.

- ^ Rochette, "Language Policies in the Roman Republic and Empire," p. 550; Stefan Zimmer, "Indo-European," in Celtic Culture: A Historical Encyclopedia (ABC-Clio, 2006), p. 961; Leonard A. Curchin, "Literacy in the Roman Provinces: Qualitative and Quantitative Data from Central Spain," American Journal of Philology 116.3 (1995), p. 464.

- ^ Varro as quoted by Isidore of Seville, Origines 15.1.63, trilingues quod et graece loquantur et latine et gallice; Edgar C. Polomé, "The Linguistic Situation in the Western Provinces of the Roman Empire," Aufstieg und Niedergang der römischen Welt II (De Gruyter, 1983), p. 527; Philip Freeman, Ireland and the Classical World (Austin: University of Texas Press, 2001), p. 15.

- ^ 106.0 106.1 Miles, "Communicating Culture, Identity, and Power," pp. 58–59.

- ^ Mullen, Southern Gaul and the Mediterranean, p. 8, especially note 10.

- ^ 108.0 108.1 108.2 Herman, Vulgar Latin, p. 12.

- ^ Mullen, Southern Gaul and the Mediterranean, pp. 266, 273.

- ^ Mullen, Southern Gaul and the Mediterranean, p. 266.

- ^ Mullen, Southern Gaul and the Mediterranean, p. 267.

- ^ Ausonius, Epicedion in patrem 9–10 (a first-person poem written in the voice of his father); J.N. Adams, Bilingualism and the Latin Language (Cambridge University Press, 2003), pp. 356–357, especially note 109, citing R.P.H. Green, The Works of Ausonius (Oxford: Clarendon Press, p. 1991), p. 276 on the view that Gaulish was the native language of Iulius Ausonius. Adams is inclined to believe that he simply spoke Latin with a Gaulish accent. See also Mullen, Southern Gaul and the Mediterranean, p. 269 (note 19).

- ^ Karmele Rotaetxe, "Basque as a Literary Language," in A Comparative History of Literatures in the Iberian Peninsula (John Benjamins, 2010), p. 446.

- ^ Clackson and Horrocks, The Blackwell History of the Latin Language, pp. 85–86.

- ^ Charles-Edwards, T. M. Wales and the Britons, 350-1064. 2012: 75. ISBN 0198217315.

- ^ Millar, "Local Cultures in the Roman Empire," p. 127.

- ^ Clackson and Horrocks, The Blackwell History of the Latin Language, pp. 86–87; Millar, "Local Cultures in the Roman Empire," pp. 128–129, expressing skepticism about identifying the non-Punic languages of North Africa as "Berber".

- ^ Wilson, "Neo-Punic and Latin Inscriptions in Roman North Africa," pp. 284, 286.

- ^ Millar, "Local Cultures in the Roman Empire," p. 129.

- ^ Millar, "Local Cultures in the Roman Empire," pp. 128–130.

- ^ 121.0 121.1 121.2 Blench, Roger. 2018. Reconciling archaeological and linguistic evidence for Berber prehistory (页面存档备份,存于互联网档案馆).

- ^ 122.0 122.1 Rochette, "Language Policies in the Roman Republic and Empire," pp. 558–559.

- ^ Sheridan, From the Nile to the Rhone, p. 226.

- ^ Sheridan, From the Nile to the Rhone, p. 225.

- ^ Miles, "Communicating Culture, Identity, and Power," p. 58; Treadgold, A History of the Byzantine State and Society, pp. 5–7.

- ^ 126.0 126.1 126.2 Millar, "Local Cultures in the Roman Empire," p. 126.

- ^ Millar, "Local Cultures in the Roman Empire," p. 127, citing Philostratus and Gregory of Nyssa.

- ^ Teresa Morgan, "Education," in The Oxford Encyclopedia of Ancient Greece and Rome (Oxford University Press, 2010), p. 18.

- ^ J.J. Wilkes, "The Roman Danube: An Archaeological Survey," Journal of Roman Studies 95 (2005), p. 124

- ^ Not to be confused with the modern Macedonian language, which is Slavonic.

- ^ 131.0 131.1 131.2 Clackson and Horrocks, The Blackwell History of the Latin Language, p. 86.

- ^ Millar, "Local Cultures in the Roman Empire," p. 126, citing also L.P. Wilkinson, Ovid Recalled (1955), ch. 10.

- ^ Goodman, Mission and Conversion, pp. 48, 130.

- ^ Mullen, introduction to Multilingualism in the Graeco-Roman Worlds, p. 18.

- ^ Goodman, Mission and Conversion, p. 48.

- ^ Goodman, Mission and Conversion, p. 79.

- ^ Goodman, Mission and Conversion, pp. 53, 78.

- ^ Goodman, Mission and Conversion, pp. 65–66.

- ^ Goodman, Mission and Conversion, p. 48.

- ^ Simon Price, "Latin Christian Apologetics: Minucius Felix, Tertullian, and Cyprian," in Apologetics in the Roman Empire: Pagans, Jews, and Christians (Oxford University Press, 1999), p. 103.

- ^ Valantasis, introduction to Religions of Late Antiquity, p. 11.

- ^ Robin Margaret Jensen, Understanding Christian Art (Routledge, 2000), p. 51; Alison E. Cooley, The Cambridge Manual of Latin Epigraphy (Cambridge University Press, 2012), p. 233.

- ^ Mark Edwards, "The Constantinian Circle and the Oration to the Saints," in Apologetics, p. 255.

- ^ Augustine, Confessions 1.14.23; Moatii, "Translation, Migration, and Communication," p. 112.

- ^ Augustine, Confessions 1.13.20 and 2.38.91; Moatti, "Translation, Migration, and Communication," p. 112, note 16.

- ^ Simon Swain, "Defending Hellenism: Philostratus, in Honour of Apollonius," in Apologetics, p. 173.

- ^ Millar, A Greek Roman Empire, pp. 97–98.

- ^ Millar, A Greek Roman Empire, p. 98.

- ^ Millar, A Greek Roman Empire, pp. 102–103.

- ^ Millar, A Greek Roman Empire, pp. 103–104.

- ^ Millar, A Greek Roman Empire, p. 104.

- ^ 152.0 152.1 Millar, A Greek Roman Empire, p. 105.

- ^ Alderik Bloom, "Linguae sacrae in Ancient and Medieval Sources: An Anthropological Approach to Ritual Language," in Multilingualism in the Graeco-Roman Worlds, p. 124, prefers "ritual" to the problematic distinction between "religion" and "magic" in antiquity.

- ^ Hans Dieter Betz, "Introduction to the Greek Magical Papyri," The Greek Magical Papyri in Translation, Including the Demotic Spells (University of Chicago Press, 1986, 1996), p. xli.

- ^ William M. Breshear, "The Greek Magical Papyri: An Introduction and Survey," Aufstieg und Niedergang der römischen Welt II 18.5 (1994), passim.

- ^ Blom, "Linguae sacrae," p. 130.

- ^ James Clackson, "Language Maintenance and Shift," in Multilingualism in the Graeco-Roman Worlds, p. 55.

- ^ Betz, introduction to "The Greek Magical Papyri," pp. xlv–xlvi; Janet H. Johnson, "Introduction to the Demotic Magical Papyri," p. lv in the same volume (page numbering of the two introductions is independent, not sequential).

- ^ Campbell Bonner, “Harpokrates (Zeus Kasios) of Pelusium,” Hesperia 15 (1946), p. 54.

- ^ In addition to the PGM, charms are common in texts from late antiquity, including the collected pharmacological recipes of Marcellus of Bordeaux; Pseudo-Apuleius, Herbarius; Sextus Placitus, Liber medicinae ex animalibus; Hippiatrica; Physica Plinii; Pseudo-Dioscurides, De herbis feminis; and the Anglo-Saxon Lacnunga. See Blom, "Linguae sacrae," p. 127, note 22. Inscriptions are found on amulets, intaglio gems, incantation bowls, curse tablets, and lamellae (metal-leaf tablets).

- ^ Fritz Graf, “Prayer in Magic and Religious Ritual,” in Magika Hiera: Ancient Greek Magic and Religion, (Oxford University Press, 1991), p. 191, and Roy Kotansky, “Incantations and Prayers for Salvation on Inscribed Greek Amulets,” also in Magika Hiera, p. 132, note 60, both on Egyptian; John G. Gager, “A New Translation of Ancient Greek and Demotic Papyri, Sometimes Called Magical,” Journal of Religion 67 (1987), p. 83 on Coptic.

- ^ Gager, “A New Translation of Ancient Greek and Demotic Papyri,", p. 83; Paul Mirecki, “The Coptic Wizard's Hoard,” Harvard Theological Review 87 (1994), pp. 457–458.

- ^ Kotansky, “Incantations and Prayers for Salvation," p. 117.

- ^ Lambert, La langue gauloise, pp. 176–178, particularly on a 3rd–4th century tablet from the Gallo-Roman town Rom that may be Celtic in a Latin context.

- ^ Breshear, "The Greek Magical Papyri," p. 3435.

- ^ Matthias Klinghardt, “Prayer Formularies for Public Recitation: Their Use and Function in Ancient Religion,” Numen 46 (1999), p. 50; Hans Dieter Betz, "Secrecy in the Greek Magical Papyri," in Secrecy and Concealment: Studies in the History of Mediterranean and Near Eastern Religions (Leiden 1995), 153–175, especially 158–164; Brashear, “The Greek Magical Papyri," p. 3434.

- ^ Richard Janko, “Forgetfulness in the Golden Tablets of Memory,” Classical Quarterly 34 (1984), pp. 89–100 on problems of oral transcription; Graf, “Prayer in Magic and Religious Ritual,” p. 191; Betz, "The Greek Magical Papyri," p. xlvi; Breshear, "The Greek Magical Papyri," pp. 3434–3438.

- ^ IGF 159; Mullen, Southern Gaul and the Mediterranean, pp. 266–267.

- ^ Adams, Bilingualism and the Latin Language, p. 194.

- ^ L.C. Youtie, "A Medical Prescription for Eye-salve," ZPE 23 (1976), pp. 121–29; Collingwood and Wright, “Roman Inscriptions of Britain I” (Oxford 1965), p. 144, no. 436.

- ^ According to Origen, Commentary on Matthew (PG 13.1757): Hebraeo acceptis adiurant daemonia; Adams, Bilingualism and the Latin Language, p. 194.

- ^ Jerome, Vita Hilarionis 13.7: videres de ore barbaro, et qui Francam tantum et Latinam linguam noverat, Syra ad purum verba resonare: Adams, Bilingualism and the Latin Language, p. 275.

- ^ MacMullen, "Provincial Languages," p. 3.

- ^ MacMullen, "Provincial Languages," pp. 2–3.

- ^ W.W. Buckland A Textbook of Roman Law from Augustus to Justinian, 3rd ed. edited by Peter Stein (Cambridge University Press, 1921, 2007), p. 9.

- ^ Digest 32.11 pr.; Ramsey MacMullen, "Provincial Languages in the Roman Empire," American Journal of Philology 87.1 (1966), p. 2.

- ^ Adolf Berg, Encyclopedic Dictionary of Roman Law (American Philosophical Society, 1980, 1991), pp. 470–471. In late antiquity, fideicommissa could be legally binding as well.

- ^ Digest 45.1.1.6; MacMullen, "Provincial Languages," p. 2.

- ^ Gaius, Institutiones 3.93; MacMullen, "Provincial Languages," pp. 2–3.

- ^ Françoise Waquet, Latin, Or, The Empire of the Sign: From the Sixteenth to the Twentieth Century (Verso, 2001; originally published 1998 in French), pp. 1–2; Kristian Jensen, "The Humanist Reform of Latin and Latin Teaching," in The Cambridge Companion to Renaissance Humanism (Cambridge University Press, 1996, 2003), pp. 63–64.

- ^ Adams, "Romanitas and the Latin Language," p. 199; Treadgold, A History of the Byzantine State and Society, pp. 5, 7.

参考文献

[编辑]参考书目

[编辑]- Adams, J.N. Bilingualism and the Latin Language. Cambridge University Press, 2003.

- Anderson, Graham The Second Sophistic: A Cultural Phenomenon in the Roman Empire. Routledge, 1993.

- Ando, Clifford. Imperial Ideology and Provincial Loyalty in the Roman Empire. University of California Press, 2000.

- Clackson, James; Horrocks, Geoffrey. The Blackwell History of the Latin Language. Blackwell, 2007, 2011.

- Goodman, Martin Welsh. Mission and Conversion: Proselytizing in the Religious History of the Roman Empire. Oxford University Press, 1994.

- Herman, József. Vulgar Latin. Translated by Roger Wright, based on the original 1975 publication in French. Pennsylvania State University Press, 2000.

- Millar, Fergus. A Greek Roman Empire: Power and Belief under Theodosius II (408–450). University of California Press, 2006.

- Mullen, Alex. Southern Gaul and the Mediterranean: Multilingualism and Multiple Identities in the Iron Age and Roman Periods. Cambridge University Press, 2013.

- Treadgold, Warren. A History of the Byzantine State and Society. Stanford University Press, 1997.

- Apologetics in the Roman Empire: Pagans, Jews, and Christians. Edited by Mark Edwards, Martin Goodman, and Simon Price, with Christopher Rowland. Oxford University Press, 1999.

- A Companion to the Latin Language. Edited by James Clackson. Blackwell, 2011.

- Multilingualism in the Graeco-Roman Worlds. Edited by Alex Mullen. Cambridge University Press, 2012.

- The Oxford Handbook of the Literatures of the Roman Empire. Edited by Daniel L. Selden and Phiroze Vasunia. Oxford University Press (most of the chapters are available online here (页面存档备份,存于互联网档案馆)).

参考文章

[编辑]- Adams, J.N. "Romanitas and the Latin Language." Classical Quarterly 53.1 (2003) 184–205.

- MacMullen, Ramsey. "Provincial Languages in the Roman Empire." American Journal of Philology 87.1 (1966) 1–17.

- Millar, Fergus. "Local Cultures in the Roman Empire: Libyan, Punic and Latin in Roman Africa." Journal of Roman Studies 58 (1968) 126–134.

- Moatti, Claudia. "Translation, Migration, and Communication in the Roman Empire: Three Aspects of Movement in History." Classical Antiquity 25.1 (2006) 109–140.

- Rance, Philip. "The De Militari Scientia or Müller Fragment as a Philological Resource. Latin in the East Roman Army and Two New Loanwords in Greek: palmarium and *recala." Glotta 86 (2010) 63–92.