菲律賓經濟

菲律賓經濟中心--馬尼拉大都會。 | |

| 貨幣 | 菲律賓比索 (菲律賓語: piso; 符號: ₱; 代碼: PHP) |

|---|---|

| 財政年度 | 自然年 |

貿易組織 | 亞開行, 亞投行, AFTA, APEC, 東盟, 東亞峰會, 24國集團, RCEP, WTO 和其它 |

國家分組 |

|

| 統計數據 | |

| 人口 | ▲ 109,035,343 (第13名)[3][4] |

| GDP | |

| GDP排名 | |

GDP增長率 | |

人均GDP | |

人均GDP排名 | |

各產業GDP | |

GDP組成 |

|

| ▼ 5.4% (2023年6月)[9] | |

| ▼ 41.2 中 (2021)[12] | |

勞動力 | |

各產業勞動力 | |

| 失業率 | |

主要產業 | |

| ▲ 95名 (容易, 2020)[17] | |

| 對外貿易 | |

| 出口 | $1152.6 億美元 (2022)[18][8][a] |

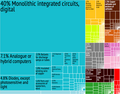

出口商品 | |

主要出口夥伴 | |

| 進口 | 1592.9 億美元 (2022)[18][8][a] |

進口商品 | |

主要進口夥伴 | |

外商直接投資存量 | |

| |

外債總額 | |

| 公共財政 | |

| −7.33% of GDP (2022)[8] | |

| 收入 |

|

| 支出 |

|

| 經濟援助 | 1.67 億美元[26] |

| ▼ 997.74 億美元 (June 2023)[31][32] | |

菲律賓是東南亞第四大規模的新興工業國家,並且是世界的新興市場之一,也是亞太地區最具發展活力的經濟體之一。[33]作為發展中經濟體,該國正致力於實現更高的工業化和經濟增長。[34]2023年,菲律賓國內生產總值估計達到24.56萬億菲律賓比索(合4409億美元),根據國際貨幣基金組織數據,按名義GDP計算,該國全球經濟規模排名第36,亞洲排名第15。

菲律賓經濟的組成以農業及工業為主,目前正從農業導向轉變為更多依賴服務業和製造業。近年來,菲律賓經濟增長迅速,轉型升級顯著。自2010年起,菲律賓經濟年均增速約6%,已成為亞太地區增長最快的經濟體之一。[35]菲律賓是聯合國、東盟、亞太經合組織、東亞峰會和世界貿易組織的創始成員國。[36]亞洲開發銀行總部位於馬尼拉東區曼達盧永的奧迪加斯中心。

菲律賓主要出口產品包括半導體和電子產品、運輸設備、服裝、化學品、銅、鎳、呂宋蕉麻、椰子油和水果。其主要貿易夥伴有日本、中國大陸、美國、新加坡、韓國、荷蘭、香港、德國、台灣和泰國。菲律賓被譽為新興「小虎」經濟體之一,與印尼、馬來西亞、越南和泰國並稱。然而,菲律賓經濟發展仍面臨減少不同地區和社會階層之間收入差距、減少腐敗以及投資基礎建設等主要問題和挑戰。

預計到2050年,菲律賓經濟規模將成為亞洲第四大、全球第19大經濟體。[37]預測到2035年,菲律賓經濟將成為全球第22大經濟體。[38]

概述

[編輯]菲律賓經濟幾十年來一直穩定增長,2014年國際貨幣基金組織將其列為世界第39大經濟體。菲律賓2022年GDP增長率高達7.6%。[39]然而,該國不是20國集團成員;相反,它被歸為新興市場或新興工業化國家的第二梯隊。根據分析師的不同,第二梯隊經濟體可以被稱為「未來11國」或「亞洲四小虎」。

下圖概述了使用國際貨幣基金組織數據顯示菲律賓國內生產總值趨勢的部分統計數據。

- 表示經濟增長

- 表示收縮/衰退

- 表示國際貨幣基金組織預測

| 年份 | GDP增長[b] | GDP,匯率 | GDP,購買力 | 菲律賓比索:美元 匯率[c] | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (十億比索) | (十億美元) | 人均

(美元) |

(十億美元) | 人均

(美元) | |||

| 2023[5] | 6.0% | 440.9 ▲ | 3,905 ▲ | 1,290.0 ▲ | 11,420 ▲ | ||

| 2022 | 7.76% | 22,023 ▲ | 404.3 ▲ | 3,623 ▲ | 1,173.1 ▲ | 10,512 ▲ | ▲ 54.47 |

| 2021 | 5.60% | 19,390 ▲ | 393.7 ▲ | 3,579 ▲ | 994.6 ▲ | 9,043 ▲ | ▼ 49.25 |

| 2020[d] | −9.50% | 17,937.6 ▼ | 361.5 ▼ | 3,298 ▼ | 919.2 ▼ | 8,389 ▼ | ▼ 49.62 |

| 2019 | 6.00% | 19,514.4 ▲ | 376.8 ▲ | 3,485 ▲ | 1,005 ▲ | 9,295 ▲ | ▼ 51.79 |

| 2018 | 6.30% | 18,262.4 ▲ | 346.8 ▲ | 3,251 ▲ | 930.0 ▲ | 8,720 ▲ | ▲ 52.66 |

| 2017 | 6.70% | 15,556.4 ▲ | 328.5 ▲ | 3,123 ▲ | 854.0 ▲ | 8,120 ▲ | ▲ 50.40 |

| 2016 | 6.90% | 15,133.5 ▲ | 318.6 ▲ | 3,073 ▲ | 798.6 ▲ | 7,703 ▲ | ▲ 47.50 |

| 2015[40] | 5.80% | 13,307.3 ▲ | 292.4 ▲ | 2,863 ▲ | 741.0 ▲ | 6,547 ▼ | ▲ 45.50 |

| 2014[40] | 6.10% | 12,645.3 ▲ | 284.8 ▲ | 2,844 ▲ | 642.8 ▲ | 6,924 ▲ | ▲ 44.40 |

| 2013[41] | 7.20% | 11,546.1 ▲ | 272.2 ▲ | 2,792 ▲ | 454.3 ▲ | 4,660 ▲ | ▲ 42.45 |

| 2012[42] | 6.80% | 10,564.9 ▲ | 250.2 ▲ | 2,611 ▲ | 419.6 ▲ | 4,380 ▲ | ▼ 42.21 |

| 2011 | 3.60% | 9,706.3 ▲ | 224.1 ▲ | 2,379 ▲ | 386.1 ▲ | 4,098 ▲ | ▼ 43.29 |

| 2010 | 7.63% | 9,003.5 ▲ | 199.6 ▲ | 2,155 ▲ | 365.3 ▲ | 3,945 ▲ | ▼ 45.09 |

| 2009 | 1.15% | 8,026.1 ▲ | 168.5 ▼ | 1,851 ▼ | 335.4 ▲ | 3,685 ▲ | ▲ 47.58 |

| 2008 | 4.15% | 7,720.9 ▲ | 173.6 ▲ | 1,919 ▲ | 329.0 ▲ | 3,636 ▲ | ▼ 44.47 |

| 2007 | 7.12% | 6,892.7 ▲ | 149.4 ▲ | 1,684 ▲ | 309.9 ▲ | 3,493 ▲ | ▼ 46.07 |

| 2006 | 5.24% | 6,271.2 ▲ | 122.2 ▲ | 1,405 ▲ | 283.5 ▲ | 3,255 ▲ | ▼ 51.29 |

| 2005 | 4.78% | 5,677.8 ▲ | 103.1 ▲ | 1,209 ▲ | 261.0 ▲ | 3,061 ▲ | ▼ 55.06 |

| 2004 | 6.70% | 5,120.4 ▲ | 91.4 ▲ | 1,093 ▲ | 242.7 ▲ | 2,905 ▲ | ▲ 56.09 |

| 2003 | 4.97% | 4,548.1 ▲ | 83.9 ▲ | 1,025 ▲ | 222.7 ▲ | 2,720 ▲ | ▲ 54.32 |

| 2002 | 3.65% | 4,198.3 ▲ | 81.4 ▲ | 1,014 ▲ | 207.8 ▲ | 2,591 ▲ | ▲ 51.60 |

| 2001 | 2.89% | 3,888.8 ▲ | 76.3 ▼ | 971 ▼ | 197.3 ▲ | 2,511 ▲ | ▲ 51.20 |

| 2000 | 4.41% | 3,580.7 ▲ | 81.0 ▼ | 1,053 ▼ | 187.5 ▲ | 2,437 ▲ | ▲ 46.44 |

| 1999 | 3.08% | 3,244.2 ▲ | 83.0 ▲ | 1,110 ▲ | 175.8 ▲ | 2,352 ▲ | ▲ 42.85 |

| 1998 | −0.58% | 2,952.8 ▲ | 73.8 ▼ | 1,009 ▼ | 168.1 ▲ | 2,297 ▼ | ▲ 40.34 |

| 1997 | 5.19% | 2,688.7 ▲ | 92.8 ▼ | 1,297 ▼ | 167.1 ▲ | 2,336 ▲ | ▲ 32.59 |

| 1996 | 5.85% | 2,406.4 ▲ | 93.5 ▲ | 1,336 ▲ | 156.1 ▲ | 2,232 ▲ | ▲ 27.15 |

| 1995 | 4.68% | 2,111.7 ▲ | 83.7 ▲ | 1,224 ▲ | 144.8 ▲ | 2,118 ▲ | ▼ 24.20 |

| 1994 | 4.39% | 1,875.7 ▲ | 71.0 ▲ | 1,052 ▲ | 135.5 ▲ | 2,007 ▲ | ▼ 24.84 |

| 1993 | 2.12% | 1,633.6 ▲ | 60.2 ▲ | 914 ▲ | 127.1 ▲ | 1,929 ▲ | ▲ 28.05 |

| 1992 | 0.34% | 1,497.5 ▲ | 58.7 ▲ | 912 ▲ | 121.8 ▲ | 1,891 ▲ | ▼ 26.44 |

| 1991 | −0.49% | 1,379.9 ▲ | 50.2 ▲ | 797 ▲ | 118.6 ▲ | 1,882 ▲ | ▲ 27.61 |

| 1990 | 3.04% | 1,190.5 ▲ | 48.9 ▲ | 796 ▲ | 115.2 ▲ | 1,873 ▲ | ▼ 22.90 |

| 1989 | 6.21% | 1,025.3 ▲ | 47.3 ▲ | 786 ▲ | 107.6 ▲ | 1,791 ▲ | ▼ 23.03 |

| 1988 | 6.75% | 885.5 ▲ | 42.0 ▲ | 715 ▲ | 97.6 ▲ | 1,663 ▲ | ▲ 23.26 |

| 1987 | 4.31% | 756.5 ▲ | 36.8 ▲ | 641 ▲ | 88.4 ▲ | 1,540 ▲ | ▲ 19.07 |

| 1986 | 3.42% | 674.6 ▲ | 33.1 ▼ | 591 ▼ | 82.4 ▲ | 1,471 ▲ | ▲ 18.42 |

| 1985 | −7.30% | 633.6 ▲ | 34.1 ▼ | 623 ▼ | 77.9 ▼ | 1,426 ▼ | ▼ 17.40 |

| 1984 | −7.31% | 581.1 ▲ | 34.8 ▼ | 652 ▼ | 81.6 ▼ | 1,530 ▼ | ▲ 17.61 |

| 1983 | 1.88% | 408.9 ▲ | 36.8 ▼ | 707 ▼ | 84.9 ▲ | 1,630 ▲ | ▲ 12.11 |

| 1982 | 3.62% | 351.4 ▲ | 41.1 ▲ | 810 ▲ | 80.1 ▲ | 1,578 ▲ | ▲ 9.47 |

| 1981 | 3.42% | 312.0 ▲ | 39.5 ▲ | 797 ▲ | 72.9 ▲ | 1,471 ▲ | ▲ 9.32 |

| 1980 | 5.15% | 270.1 ▲ | 35.9 ▲ | 744 ▲ | 64.4 ▲ | 1,334 ▲ | ▲ 7.78 |

| 1979 | 5.60% | ||||||

| 1978 | 5.20% | ||||||

| 1977 | 5.60% | ||||||

| 1976 | 8.00% | ||||||

| 1975 | 6.40% | ||||||

| 1974 | 5.00% | ||||||

| 1973 | 9.20% | ||||||

| 1972 | 4.80% | ||||||

| 1971 | 4.90% | ||||||

| 1970 | 4.60% | ||||||

按行業劃分的構成

[編輯]

作為一個新興工業化國家,菲律賓仍然是一個農業部門龐大的經濟體;然而,該國的服務業最近有所擴張。[46]大部分工業部門都以電子產品和其他高科技零部件製造的加工和組裝業務為基礎,這些業務通常來自外國跨國公司。

出國工作的菲律賓人(稱為菲律賓海外勞工或OFW)是經濟的重要貢獻者,但並未反映在以下國內經濟部門討論中。菲律賓近期的經濟增長也歸功於海外菲工的匯款,導致惠譽國際和標準普爾等信用評級機構提升了投資地位。[47]1994年海外菲律賓人匯往菲律賓的匯款價值超過20億美元,[48]這一數字大幅增加至2022年創紀錄的361.4億美元。[49][50]

農業

[編輯]截至2022年[update],第一產業雇用了24%的菲律賓勞動力,[51]占國內生產總值(GDP)的8.9%。[52]第一產業活動種類繁多,既有自給自足的小規模耕作和捕魚,也有以出口為主的大型商業企業。

菲律賓是世界第三大椰子生產國,也是世界最大的椰子產品出口國。[53]椰子生產一般集中在中型農場。[54]菲律賓也是世界第三大菠蘿生產國,2021年菠蘿產量為2,862,000公噸。[55]

菲律賓的大米生產對該國的糧食供應和經濟都非常重要。截至2019年[update],菲律賓是世界第八大水稻生產國,占全球水稻產量的2.5%。[56]水稻是最重要的糧食作物,是該國大部分地區的主食;[57]它廣泛地種植於呂宋島中部、西米沙鄢群島、卡加延河谷、索科斯克薩爾根和伊羅戈地區。[58][59]

菲律賓是世界上最大的蔗糖生產國之一。[60]全國8個大區中至少有17個省份種植甘蔗作物,其中內格羅斯島地區占全國總產量的一半。截至2012-2013種植年度,有29家工廠正在運營,具體情況如下:內格羅斯有13家工廠,呂宋島有6家工廠,班乃有4家工廠,東米沙鄢群島有3家工廠,棉蘭老島有3家工廠。[61]全國有超過360,000至390,000公頃(890,000至960,000英畝)的土地用於甘蔗生產。最大的甘蔗種植面積位於內格羅斯島地區,占甘蔗種植面積的51%。其次是棉蘭老島,占20%;呂宋島17%;班乃(Panay)占7%,東米沙鄢(Eastern Visayas)占4%。[62]

-

達皮坦的一片椰林

-

帕達達的香蕉種植園

-

巴科洛德的大片甘蔗種植園

-

布拉干省的一片稻田

-

拉古納市場上的菠蘿

-

鳳梨出口品

-

霧宿的糖廠

-

農村梯田

汽車和航空航天

[編輯]梅賽德斯·奔馳、寶馬和沃爾沃汽車使用的ABS是在菲律賓製造的。菲律賓的汽車銷量從上年的268,488輛增至2022年的352,596輛。[63]豐田在該國銷售的汽車最多;其次是三菱、福特、日產和鈴木。本田和鈴木在該國生產摩托車。2010年代左右以來,多個中國汽車品牌進入菲律賓市場;其中包括奇瑞和福田汽車。[64][65]

菲律賓的航空航天產品主要供應出口市場,包括為波音和空客製造的飛機製造零部件。穆格是最大的航空航天製造商,總部位於科迪勒拉地區的碧瑤;該公司在其工廠生產製造飛機執行器。2019年菲律賓航空航天產品出口總額達7.8億美元。[66]

電子產品

[編輯]

德州儀器位於碧瑤的工廠已運營20年,是全球最大的數字信號處理芯片生產商。[67][68]德州儀器的碧瑤工廠生產全球諾基亞手機使用的所有芯片和愛立信手機使用的80%的芯片。[69]東芝硬盤驅動器在拉古納聖羅莎製造。[70]打印機製造商利盟在宿務市設有一家工廠。[71]電子和其他輕工業集中在內湖省、甲美地省、八打雁省和卡拉巴松省及其他省份,其中菲律賓南部有大量電子工業和其他輕工業,占該國出口的大部分。[72]

根據菲律賓最大的外國和菲律賓電子公司組織SEIPI,菲律賓電子行業分為(73%)半導體製造服務(SMS)和(27%)電子製造服務(EMS)。[73]2022年,電子產品繼續成為該國第一大出口產品,總收入達456.6億美元,占貨物出口總額的57.8%。

採礦和開採

[編輯]

菲律賓礦產和地熱能源資源豐富。2019年,它利用地熱源發電1,928兆瓦(2,585,000馬力)(占總發電量的7.55%)。[74]1989年,巴拉望島附近的馬拉帕亞油田發現了天然氣儲量,三座天然氣發電廠正在利用該油田發電。[75]菲律賓的金、鎳、銅、鈀和鉻鐵礦礦藏位居世界前列。[76][77]其他重要的礦物包括銀、煤、石膏和硫磺。存在大量粘土、石灰石、大理石、二氧化硅和磷酸鹽礦藏。

非金屬礦產量約占礦業總產量的60%,1993年至1998年間,非金屬礦產對行業產量的穩定增長做出了重大貢獻,產值增長了58%。2020年菲律賓礦產出口額達42.2億美元。[78]金屬價格低、生產成本高、基礎設施投資不足以及新採礦法面臨的挑戰導致採礦業整體下滑。

該行業自2004年底開始反彈,當時最高法院維持了一項允許外國擁有菲律賓礦業公司所有權的重要法律的合憲性。[79]2019年,該國是世界第二大鎳生產國[80]和世界第四大鈷生產國。[81]根據菲律賓統計局的數據,到2022年,被評估為A級的四種主要金屬礦物(即銅、鉻鐵礦、金和鎳)的總貨幣價值為90.1億美元。[82]A級礦產資源具有商業可開採性,這可能有助於其經濟發展。

離岸外包

[編輯]

商業流程委外(BPO)和呼叫中心行業為菲律賓的經濟增長做出了貢獻,致使惠譽和標準普爾等信用評級機構調升了其投資地位級別。[83]2008年,菲律賓已超越印度,成為商業流程委外(BPO)領域的全球領先者。[84][85]該行業創造了100,000個就業機會,2005年總收入達到9.6億美元。2011年,BPO行業就業人數激增至700,000多人,[86]並為不斷壯大的中產階級做出了貢獻;到2022年,這一數字將增加到約130萬名員工。[87]BPO設施集中在菲律賓各地經濟區的IT園區和中心,主要集中在六個「卓越中心」:馬尼拉大都會、宿務大都會、克拉克都會區、巴科洛德、達沃市和伊洛伊洛市;其他被視為BPO的「下一波城市」的地區包括碧瑤、卡加延德奧羅、達斯馬里尼亞斯、杜馬蓋地市、利帕、納加、聖羅莎、拉古納。[88]美國排名前十的BPO公司大多數在菲律賓開展業務。[89]

呼叫中心始於菲律賓,作為電子郵件回復和管理服務的簡單提供商,是就業的主要來源。呼叫中心服務包括客戶關係,範圍包括旅行服務、技術支持、教育、客戶服務、金融服務、在線業務到客戶支持以及在線企業對企業支持。菲律賓因其許多外包優勢而被視為首選地點,例如運營和勞動力成本較低、相當多的人英語口語熟練程度高以及受過高等教育的勞動力資源。[90][91]

BPO行業的增長是由菲律賓政府推動的。該行業被菲律賓發展計劃列為十大高潛力和優先發展領域之一。為了進一步吸引投資者,政府計劃包括不同的激勵措施,例如免稅期、免稅和簡化進出口程序。此外,還為BPO申請人提供培訓。[92]

可再生能源

[編輯]

菲律賓在太陽能方面擁有巨大潛力;然而,截至2021年,國內生產的大部分電力都是基於化石燃料資源,尤其是煤炭。[93][94]2019年,菲律賓生產了7,399瓦特(9,922,000匹馬力)的可再生能源。至2022年11月15日為止,該國可再生能源(RE)行業的外資持股比例從目前的40%上限提高到100%,菲律賓允許外資進入可再生能源行業,因為能源部的目標是到2030年將可再生能源在國家發電結構中的比例從目前的22%提高到35%,到2040年提高到50%。[95]丹麥哥本哈根基礎建設基金(CIP)將投資50億美元開發三個海上風能項目,潛在發電能力為2,000兆瓦(2,700,000馬力),分別位於北甘馬林和南甘馬林(1,000兆瓦)、北薩馬(650兆瓦)、邦阿西楠和拉烏尼翁(350兆瓦)。[96]2022年,可再生能源在能源結構中所占比例為22.8%。[97]

造船業和船舶維修

[編輯]

菲律賓是全球造船業[98]的主要參與者,2021年有118家註冊造船廠,[99]分布在蘇比克、宿務、巴丹、納沃塔斯和八打雁。自2010年以來,菲律賓一直是第四大造船國。[100][101]蘇比克製造的貨輪出口到航運運營商所在的國家。韓國韓進於2007年開始在蘇比克生產德國和希臘航運運營商訂購的20艘船舶。[102]蘇比克的造船廠還建造散貨船、集裝箱船和大型客輪。桑托斯將軍港的造船廠主要從事船舶維修和保養。[103]

馬尼拉四面環海,擁有豐富的天然深海港口,非常適合開發為生產、建設和維修基地。在船舶維修領域,位於大馬尼拉的納沃塔斯綜合體預計可容納96艘船舶進行維修。[104]造船業是菲律賓海洋遺產的一部分;[105]在2021年占國內生產總值3.6%的海洋產業中,造船業貢獻了近30%的收入。[106][107]

-

出口品

-

吉普尼車

參照

[編輯]參考文獻

[編輯]- ^ 世界经济展望数据库,2019 年 4 月. 國際貨幣基金組織. [September 29, 2019]. (原始內容存檔於2019-12-22).

- ^ 世界银行国家组和贷款组. World Bank. [September 29, 2019]. (原始內容存檔於2019-10-28).

- ^ 菲律宾 2021 年人口增长率为 70 年来最低. 菲律賓通訊社. [December 27, 2021]. (原始內容存檔於2022-01-08).

- ^ Philippine Population Clock (Live). Commission on Population and Development. [February 2, 2021]. (原始內容存檔於May 5, 2021).

- ^ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 5.4 World Economic Outlook Database, April 2023. International Monetary Fund. [April 11, 2023]. (原始內容存檔於2023-04-11).

- ^ 6.0 6.1 World Economic Outlook April 2023 - A Rocky Recovery. International Monetary Fund: 146. [April 11, 2023]. (原始內容存檔於2023-07-26).

- ^ GDP Expands by 6.4 Percent in the First Quarter of 2023. PSA (新聞稿). [May 11, 2023]. (原始內容存檔於May 12, 2023).

- ^ 8.0 8.1 8.2 8.3 8.4 8.5 8.6 8.7 PHILIPPINES: SELECTED ECONOMIC AND FINANCIAL INDICATORS (PDF). Bangko Sentral ng Pilipinas. [July 7, 2023]. (原始內容存檔 (PDF)於July 11, 2023).

- ^ Summary Inflation Report Consumer Price Index (2018=100): June 2023 (新聞稿). PSA. [July 5, 2023]. (原始內容存檔於2023-07-27).

- ^ 2021 年菲律宾贫困人口比例. PSA (新聞稿). [August 15, 2022]. (原始內容存檔於August 15, 2022).

- ^ Poverty headcount ratio at $2.15 a day (2017 PPP) (% of population). 世界銀行. [November 3, 2019]. (原始內容存檔於2022-06-29).

- ^ Highlights of the Preliminary Results of the 2021 Annual Family Income and Expenditure Survey (新聞稿). PSA. [August 15, 2022]. (原始內容存檔於May 16, 2023).

- ^ 13.0 13.1 Human Development Index (HDI). Human Development Reports (報告) (聯合國開發計劃署). [October 10, 2022]. (原始內容存檔於2019-12-15).

- ^ 14.0 14.1 14.2 14.3 14.4 14.5 Unemployment Rate in May 2023 was Estimated at 4.3 Percent (新聞稿). PSA. [July 7, 2023]. (原始內容存檔於2023-08-04).

- ^ Manufacturing. Industry.gov.ph. Department of Trade and Industry. [February 25, 2023]. (原始內容存檔於February 25, 2023).

- ^ 2018 Census of Philippine Business and Industry: Economy-Wide. PSA. [November 9, 2020]. (原始內容存檔於2023-02-25).

- ^ Philippines climbs to 95th spot in World Bank's 'Doing Business' rankings. The Philippine Star. [November 3, 2019]. (原始內容存檔於2019-11-03).

- ^ 18.0 18.1 Philippines (PHL) Exports, Imports, and Trade Partners. The Observatory of Economic Complexity. [2023-07-31]. (原始內容存檔於2023-03-21).

- ^ 19.0 19.1 Highlights of the 2022 Foreign Trade Statistics for Agricultural Commodities in the Philippines: Final Result. PSA (新聞稿). [April 24, 2023]. (原始內容存檔於May 3, 2023).

- ^ 20.0 20.1 20.2 20.3 Highlights of the 2022 Annual International Merchandise Trade Statistics of the Philippines. PSA (新聞稿). [April 1, 2023]. (原始內容存檔於May 3, 2023).

- ^ 21.0 21.1 World Investment Report 2023: Philippines (PDF). United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (報告). [July 5, 2023]. (原始內容存檔 (PDF)於July 11, 2023).

- ^ Current account deficit soars to record high $17.8 billion in 2022. The Philippine Star. [March 18, 2023]. (原始內容存檔於2023-05-06).

- ^ BSP External Debt FAQs (PDF). Bangko Sentral ng Pilipinas. [January 1, 2023]. (原始內容 (PDF)存檔於March 13, 2023).

- ^ Philippines external debt hits record high $111.3 billion in 2022. The Philippine Star. [March 20, 2023]. (原始內容存檔於2023-04-12).

- ^ Villanueva, Joann. PH PH debt-to-GDP ratio still not at alarming level. 菲律賓通訊社. [February 3, 2023]. (原始內容存檔於February 3, 2023).

- ^ NEDA: Foreign aid releases slightly increased in 2011 | Inquirer Business. Philippine Daily Inquirer. March 5, 2012 [October 12, 2012]. (原始內容存檔於2012-04-19).

- ^ Philippines: Japan Credit Rating Agency, Ltd. (PDF). JCR. [March 10, 2023]. (原始內容存檔 (PDF)於2023-03-11).

- ^ S&P Global reaffirms PH rating at BBB+. Department of Finance (報告). [November 17, 2022]. (原始內容存檔於2022-12-09).

- ^ Rating Action: Moody's upgrades Philippines to Baa2, outlook stable. Moody's Investors Service. September 11, 2022 [September 12, 2022]. (原始內容存檔於2022-09-15).

- ^ Philippines. Fitch Ratings. [May 22, 2023]. (原始內容存檔於2023-02-19).

- ^ Special Data Dissemination Standards, Economic and Financial Data for the Philippines. Bangko Sentral ng Pilipinas. [July 23, 2022]. (原始內容存檔於2023-05-30).

- ^ Gross International Reserves. Bangko Sentral ng Pilipinas. [January 1, 2023]. (原始內容存檔於2023-02-18).

- ^ The World Bank in the Philippines. World Bank. [March 21, 2022]. (原始內容存檔於2023-08-14).

- ^ Philippine Development Plan 2023-2028 (PDF). National Economic and Development Authority. [January 1, 2023]. (原始內容存檔 (PDF)於2023-05-22).

- ^ Bajpai, Prableen. Emerging Markets: Analyzing the Philippines's GDP. Investopedia. [March 17, 2022]. (原始內容存檔於April 2, 2023).

- ^ The Philippines: September 1999. World Trade Organization. September 20, 1999 [2023-07-31]. (原始內容存檔於2023-05-10).

- ^ "The World in 2050.". PwC. [February 1, 2017]. (原始內容存檔於2020-11-17).

- ^ Philippines poised to be 22nd biggest economy in the world by 2035 — CEBR. BusinessWorld. December 28, 2020 [December 29, 2020]. (原始內容存檔於May 20, 2022).

- ^ Esmael, Lisbet. 1976年以来最强劲:希盟2022年经济增长7.6%. CNN菲律賓. January 26, 2023 [March 18, 2023]. (原始內容存檔於January 26, 2023).

- ^ 40.0 40.1 National Accounts of the Philippines (NAP). National Statistical Coordination Board. (原始內容存檔於November 13, 2012).

- ^ Report for Selected Countries and Subjects. International Monetary Fund. [March 3, 2015]. (原始內容存檔於2015-05-06).

- ^ Report for Selected Countries and Subjects. International Monetary Fund. Imf.org. April 16, 2013 [April 19, 2013]. (原始內容存檔於2013-08-23).

- ^ 國際貨幣基金組織。 (2010 年 10 月)。 菲律賓證券交易所,它是東南亞最古老的證券交易所之一,自 1927 年成立以來一直持續運營。目前擁有兩個交易大廳,其中一個位於 [[馬卡蒂] 的阿亞拉塔一號 ]] 中央商務區,其總部位於巴石。 PSE 由 15 人組成的董事會組成,主席為 Jose T. Pardo。 ([//web.archive.org/web/20110628221817/http://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/weo/2010/02/weodata/weorept.aspx?pr.x=38&pr.y=9&sy=1980&ey=2015&scsm=1&ssd=1&sort=country&ds=.&br=1&c=566&s=NGDP_R%2CNGDP_RPCH%2CNGDP%2CNGDPD%2CNGDP_D%2CNGDPRPC%2CNGDPPC%2CNGDPDPC%2CPPPGDP%2CPPPPC%2CPPPSH%2CPPPEX%2CPCPI%2CPCPIPCH%2CPCPIE%2CPCPIEPCH%2CLUR%2CLP%2CGGR%2CGGR_NGDP%2CGGX%2CGGX_NGDP%2CGGXCNL%2CGGXCNL_NGDP%2CGGXONLB%2CGGXONLB_NGDP%2CGGXWDG%2CGGXWDG_NGDP%2CNGDP_FY%2CBCA%2CBCA_NGDPD&grp=0&a= 頁面存檔備份,存於網際網路檔案館) World Economic Outlook Data, By Country – Philippines: [selected annual data for 1980–2015]]. Retrieved 2011-01-31 from the World Economic Outlook Database.

- ^ The World Economic Outlook (WEO) Database April 2002 – Real Gross Domestic Product (annual percent change) – All countries. International Monetary Fund. April 2002 [2023-08-01]. (原始內容存檔於2011-06-28).

- ^ Philippines: Selected Economic and Financial Indicators (2018=100) (PDF). Bangko Sentral ng Pilipinas. [March 3, 2023]. (原始內容存檔 (PDF)於March 6, 2023).

- ^ Philippines, The World Factbook (Central Intelligence Agency), September 27, 2021 [October 11, 2021], (原始內容存檔於2021-08-20) (英語)

- ^ del Rosario, King. MBA Buzz: More Funds in the Philippines. Globis. [June 11, 2013]. (原始內容存檔於April 7, 2014).

- ^ Starr, Kevin. Coast of Dreams. Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group. June 22, 2011: 159 [2023-08-01]. ISBN 978-0-307-79526-7. (原始內容存檔於2023-02-18).

- ^ Arceo, Mayvelin U. OFW remittances hit record high in December. The Manila Times. [February 16, 2023]. (原始內容存檔於2023-03-08).

- ^ Remittances hit record high of $36.1 billion in 2022. The Philippine Star. [February 16, 2023]. (原始內容存檔於2023-02-15).

- ^ Employment situation as of December 2022. Philippine Statistics Authority (新聞稿). [February 8, 2023]. (原始內容存檔於2023-02-08).

- ^ Agriculture shared (%) of the total GDP. Philippine Statistics Authority. [February 22, 2023]. (原始內容存檔於2023-04-05).

- ^ Behnassi, Mohamed; Gupta, Himangana; Baig, Mirza Barjees; Noorka, Ijaz Rasool. The Food Security, Biodiversity, and Climate Nexus. Springer Nature. October 20, 2022: 252 [March 3, 2023]. ISBN 978-3-031-12586-7. (原始內容存檔於2023-04-05) (英語).

- ^ Hayami, Yūjirō; Quisumbing, Maria Agnes R.; Adriano, Lourdes S. Toward an alternative land reform paradigm: a Philippine perspective. Ateneo de Manila University Press. 1990: 108 [November 15, 2011]. ISBN 978-971-11-3096-1. (原始內容存檔於2023-02-18).

- ^ World pineapple production by Country. Statista. [September 27, 2020]. (原始內容存檔於2020-07-13).

- ^ This is how much rice is produced around the world - and the countries that grow the most. World Economic Forum. March 9, 2022 [April 25, 2023]. (原始內容存檔於March 9, 2022) (英語).

- ^ Narvaez-Soriano, Nora. A Guide to Food Selection, Preparation and Preservation. Rex Book Store, Inc. 1994: 120 [March 11, 2023]. ISBN 978-971-23-0114-8 (英語).

- ^ Top 10 Rice Farming Regions in the Philippines. Mindanao Times. January 30, 2022 [April 25, 2023]. (原始內容存檔於January 31, 2022).

- ^ Agoot, Liza. PH logs highest rice production rate at 19.44M metric tons: DA. Philippine News Agency. December 22, 2020 [April 25, 2023]. (原始內容存檔於December 27, 2020).

- ^ ESS Website ESS : Statistics home. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. [March 3, 2015]. (原始內容存檔於2012-01-25).

- ^ Historical Statistics. 糖業監管局. [March 3, 2015]. (原始內容存檔於2019-07-16).

- ^ Master Plan For the Philippine Sugar Industry. Sugar Master Plan Foundation, Inc. 2010: 7.

- ^ PH auto industry posts 31% sales growth in 2022. Manila Bulletin. January 12, 2023 [March 18, 2023]. (原始內容存檔於January 11, 2023) (英語).

- ^ Panganiban, Ira. Chinese cars and ride-hailing cars. The Manila Times. March 14, 2023 [April 7, 2023]. (原始內容存檔於March 14, 2023) (英語).

- ^ Tan, Alyssa Nicole O. Foton plans expansion with six new dealership locations. BusinessWorld. May 22, 2022 [April 7, 2023]. (原始內容存檔於May 22, 2022).

- ^ Aerospace Industry supports RCEP. Philippine Information Agency. January 27, 2022 [March 3, 2023]. (原始內容存檔於2023-03-03).

- ^ Gatdula, Donnabelle. TransCo installs 50-MVA transformer in Benguet. The Philippine Star. January 30, 2006 [April 23, 2023]. (原始內容存檔於April 23, 2023).

- ^ Chiu, Rey Anthony. Intel Phils manager debunks negative perception. Philippine Information Agency (新聞稿). July 13, 2007 [April 23, 2023]. (原始內容存檔於April 23, 2023).

- ^ Texas Instruments in Baguio retrenches 392 employees. C114 - China Communication Network. January 9, 2009 [October 12, 2012]. (原始內容存檔於July 6, 2010).

- ^ Osorio, Ma. Elisa. Toshiba unit to expand RP operations. The Philippine Star. February 20, 2009 [April 23, 2023]. (原始內容存檔於November 26, 2020).

- ^ Contact Lexmark. Lexmark Philippines. [April 7, 2023]. (原始內容存檔於December 6, 2022) (英語).

- ^ Reyes-Macasaquit, Mari-Len. 4: Case Study of the Electronics Industry in the Philippines: Linkages and Innovation. Intarakumnerd (編). Fostering Production and Science and Technology Linkages to Stimulates Innovation in ASEAN (PDF) (報告). Economic Research Institute for ASEAN and East Asia: 146–147. 2010 [April 23, 2023]. (原始內容 (PDF)存檔於August 19, 2019).

- ^ Homepage |. Semiconductor and Electronics Industries in the Philippines Foundation. [2023-08-02]. (原始內容存檔於2023-09-20).

- ^ Power Planning and Development Division, Electric Power Industry Management Bureau. 2019 Power Situation Report (PDF). Department of Energy (報告): 7. [February 19, 2023]. (原始內容存檔 (PDF)於April 2, 2023).

- ^ The Report: Philippines 2016. Oxford Business Group. April 8, 2016: 122 [February 27, 2023]. ISBN 978-1-910068-55-7. (原始內容存檔於2023-04-25) (英語).

- ^ Schneider, Keith. The Philippines, a nation rich in precious metals, encounters powerful opposition to mining. Mongabay. June 8, 2017 [July 18, 2020]. (原始內容存檔於July 10, 2017).

- ^ Cinco, Maricar. Firm sees metal costlier than gold in Romblon sea. Philippine Daily Inquirer. June 3, 2016 [July 24, 2020]. (原始內容存檔於July 24, 2020).

- ^ Teves, Catherine. Total mineral product export earnings rise. Philippine News Agency. December 11, 2020 [April 13, 2023]. (原始內容存檔於December 13, 2020).

- ^ Conde, Carlos H. Court ruling in Philippines buoys mining sector there. The New York Times. December 3, 2004 [January 15, 2021]. (原始內容存檔於2021-01-22).

- ^ McRae, Michele E. Mineral Commodity Summaries: Nickel (PDF) (報告). United States Geological Survey. January 2021. (原始內容 (PDF)存檔於February 16, 2021).

- ^ Shedd, Kim B. Mineral Commodity Summaries: Cobalt (PDF) (報告). United States Geological Survey. January 2021. (原始內容 (PDF)存檔於February 13, 2021).

- ^ Philippines’ Class A Gold, Copper, Nickel and Chromite Resources Valued at PhP 491.19 Billion in 2022. PSA (新聞稿). [July 6, 2023]. (原始內容存檔於July 6, 2023).

- ^ del Rosario, King. MBA Buzz: More Funds in the Philippines. Globis. [June 11, 2013]. (原始內容存檔於April 7, 2014).

- ^ IBM Global Business Services. (October 2008). Global Location Trends – 2008 Annual Report[永久失效連結]

- ^ Balana, Cynthia D. and Lawrence de Guzman. (December 5, 2008). It's official: Philippines bests India as No. 1 in BPO 網際網路檔案館的存檔,存檔日期September 26, 2012,.. The Philippine Daily Inquirer.

- ^ Garcia, Cathy Rose A. BPO industry to generate 100,000 jobs this year: WB. ABS-CBN News. March 21, 2012 [2023-08-04]. (原始內容存檔於2019-04-12).

- ^ Arenas, Guillermo; Coulibaly, Souleymane. A New Dawn for Global Value Chain Participation in the Philippines. World Bank Publications. November 14, 2022: 28–29 [February 27, 2023]. ISBN 978-1-4648-1848-6. (原始內容存檔於2023-03-18) (英語).

- ^ Bacolod still 'center of excellence' for IT-BPO. SunStar. July 2, 2020 [April 27, 2023]. (原始內容存檔於August 8, 2020) (英語).

- ^ foreign companies eye local BPO sector. Philippine Daily Inquirer. [August 5, 2015]. (原始內容存檔於2018-08-12).

- ^ Friginal, Eric. The Language of Outsourced Call Centers: A Corpus-based Study of Cross-cultural Interaction. John Benjamins Publishing. 2009: 17 [April 13, 2023]. ISBN 978-90-272-2308-1. (原始內容存檔於2023-05-29) (英語).

- ^ Snow, Donald M.; Haney, Patrick J. U.S. Foreign Policy: Back to the Water's Edge. Rowman & Littlefield. August 2, 2017: 262 [April 13, 2023]. ISBN 978-1-4422-6818-0. (原始內容存檔於2023-04-13) (英語).

- ^ The Philippines – Poised for Growth Through BPO. DCR TrendLine. April 1, 2015 [November 10, 2015]. (原始內容存檔於November 17, 2015).

- ^ Overland, Indra; Sagbakken, Haakon Fossum; Chan, Hoy-Yen; Merdekawati, Monika; Suryadi, Beni; Utama, Nuki Agya; Vakulchuk, Roman. The ASEAN climate and energy paradox. Energy and Climate Change. December 2021, 2: 100019. doi:10.1016/j.egycc.2020.100019. hdl:11250/2734506

.

.

- ^ Series of Economic Fora Session 6: Energy Services and Renewable Energy in the New Normal. Department of the Interior and Local Government (Philippines), Center for Research and Communication. [2023-08-21]. (原始內容存檔於2021-12-04).

- ^ DOE opens RE for full foreign ownership. Manila Bulletin. [November 16, 2022]. (原始內容存檔於2023-03-07).

- ^ Crismundo, Kris. Danish firm investing $5-B for offshore wind projects in PH. Philippine News Agency. [March 30, 2023]. (原始內容存檔於2023-05-31).

- ^ DOE to achieve renewable energy goals via reforms. Philippine News Agency. [February 3, 2023]. (原始內容存檔於2023-03-07).

- ^ Reyes, Daniel A. The Philippine Shipbuilding Industry (PDF). Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (報告) (Paris, France). November 27, 2013 [April 26, 2023]. (原始內容 (PDF)存檔於September 10, 2015).

- ^ Robust shipbuilding industry key to making PHL a maritime power. BusinessWorld. April 17, 2023 [April 26, 2023]. (原始內容存檔於April 17, 2023).

- ^ Registered Shipbuilding and Ship Repair Entity With Facilities, Manpower & Capitalization in Central Office (as of December 2017) (PDF). Maritime Industry Authority. [August 9, 2023]. (原始內容 (PDF)存檔於January 17, 2022).

- ^ Philippines Shipbuilding Hub In Asia-Pacific. Manila Bulletin. December 4, 2012 [March 3, 2015]. (原始內容存檔於April 4, 2015) –透過Yahoo! News Philippines.

- ^ New era as shipbuilding production begins in the Philippines. Shipping Times. [March 3, 2015]. (原始內容存檔於May 9, 2007).

- ^ Poole, William. Big ambitions for Philippines shipbuilding. Baird Maritime. [March 3, 2015]. (原始內容存檔於April 2, 2015).

- ^ Filipino firm invests P259M for shipyard in Navotas. BusinessMirror. [January 12, 2013]. (原始內容存檔於December 16, 2012).

- ^ How shipbuilding contributes to PH economic growth. The Manila Times. March 19, 2022 [April 26, 2023]. (原始內容存檔於March 26, 2022) (英語).

- ^ Infographics POESA 2021 (PDF). PSA (新聞稿). [December 16, 2022]. (原始內容存檔 (PDF)於2023-03-21).

- ^ Ocean-based Industries Grew by 6.7 Percent, Accounted for 3.6 Percent of GDP in 2021. PSA (新聞稿). [December 16, 2022]. (原始內容存檔於2023-05-15).